I am glad to announce the appearance of the paperback version of my book Violent Capitalism and Hybrid Identity in the Eastern Congo with Cambridge University Press. The book comes at a time of great turmoil in Congo’s north-east, where the end of armed conflict is not at all in sight, as recent reports from Ituri and le Grand Nord reveal. Reading through the detailed colonial and postcolonial history of this region makes one aware of the underlying dynamics of this armed conflict, which finds its origins in a series of intricate relations between regional politics, cross-border economies and capital accumulation. As Janosch Kullenberg writes in a recent review: the book moves beyond the “stereotypical and simplistic understandings about state failure and chronic violence in central Africa [which] have not led to great insights about either the mechanisms at work, or the emerging orders.” Instead the recent reports about continued violence in Eastern Congo make it worthwhile to approach this “constant crisis” through the long-term consequences of every day decision-making through a “ethnography of critical life worlds”.

Category Archives: war

The Terror of Peace

Please allow me to post somewhat lately this reply to my joint piece with Christoph Vogel about the transformative effects of conflict minerals regulation in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). I rediscovered the piece just as the bodies of two UN experts have been found in Kasai, along with their driver and translator. Human Rights Watch expert Anneke Van Woudenberg described this unprecedented attack as “devastating news” and “a blow to the crucial work on … sanctions violations” (on twitter). Although the two reports are unrelated, the New York Times reported on the day of their disappearance the arrest of seven Congolese Army officers who were charged with war crimes, after a video surfaced last month that appeared to show uniformed soldiers opening fire on a group of civilians in a massacre that left at least 13 people dead, including women, and possibly children. Apparently the UN experts were investigating mass graves in the same area… These terrible news show how, rather than expressing a “the privilege of an academic viewpoint“, investigations such as these into the messiness of current ‘post-war’ tensions -including around resource access- continue not only to be necessary, but are often paid dear by those who, like those UN experts, have the courage to denounce abuse.

Sacrifice

Further to my previous post about Brussels some days ago, two apparently unrelated analyses appear to confirm my observations about the reasons behind IS expansion. According to terrorism expert Hassan Hassan, the strategy of hitting targets in Europe, far removed from their operational bases in the Middle East and Northern Africa, is increasingly unrelated to the loss of terrain they are experiencing in the latter. On the contrary, the attacks in Paris and Brussels show how IS is trying to take control over former Al Qaeda networks by aligning and associating themselves with the latter’s militants.

Further to my previous post about Brussels some days ago, two apparently unrelated analyses appear to confirm my observations about the reasons behind IS expansion. According to terrorism expert Hassan Hassan, the strategy of hitting targets in Europe, far removed from their operational bases in the Middle East and Northern Africa, is increasingly unrelated to the loss of terrain they are experiencing in the latter. On the contrary, the attacks in Paris and Brussels show how IS is trying to take control over former Al Qaeda networks by aligning and associating themselves with the latter’s militants.

In an unrelated analysis, Scott Atran -an anthropologist working in France and the UK- warns not to underestimate the ideological traction of the IS Caliphate. In the poor neighbourhoods of Casablanca and Tetuan, as in the Parisian banlieus, he and his colleagues encountered a widespread acceptance, if not a sharing, of IS values as well as the brutal violence committed in its name. Despite some of the factual mistakes in Atran’s text (which are discussed in part on the Aeon forum) the key message is valid and lays in what Edmund Burke, in a different context, calls the attraction for the sublime -or the fascination to fight for a glorious and unifying cause.

Far from being miserable paupers, or a rejected Lumpenproletariat (as Diego Gambetta showed for other historical examples), IS suicide bombers not only share this fascination, but they are also ready to make the ultimate sacrifice in favour of this greater good as well as for their group of companions with whom they share intimate relationships (Atran talks about a fusion of identity in this regard). In this sense it does not come as a big surprise that the large majority of IS recruits are mobilised through their proper families, the French centre against religious radicalisation (or CPDSI) reveals. Rather than more police and camouflage on the streets, therefore, what might be needed instead are closer contacts with such families at risk as well as community leaders. In their unwillingness to also address the socio-psychological causes of this terrorist (or, as Atran provocatively says, “revolutionary”) struggle, European leaders continue to play into the cards of the IS military leadership, which is becoming increasingly apt in exploiting this diminishing grey zone between the sovereign life of post-modern (neo)liberal democracies, and the killing of this life in the name of revolutionary sacrifice…

After Brussels

I’ve been willing to write something about Brussels for a while now, but somehow I missed the words. Other than the tragic loss of 32 lives, the wounding of many others, as well as the fact that the attack took place in Belgium, where I was born, in an airport where I’ve passed dozens of times, a metro I regularly took, perhaps the most sobering aspect of the 22 March attacks has been the widespread resignation with which they have been received. Contrarily to Paris and New York, there were no patriotic speeches on the rubble of crumbled buildings; and few were the propositions to ‘smoke out the terrorists’ from their ‘caves’ and hideouts.

One reason might be the awareness that the neuralgic centre of the attacks lay a few miles from where they took place this time. In that respect, it’s been ironic how Brussels, and Belgium by extension, has quickly acquired the epithet of the ‘failed state’ in quite similar ways Afghanistan or Somalia continue to be described by some conservative think-tanks like the Fund for Peace. Driven by almost revanchist undertones (for example in these reflections by Tim King and former war reporter Teun Voeten for Politico), Belgium’s dysfunctional federalism is taken as a mirror for the ‘lawlessness’ and rising radicalism in the Brussels neighbourhood known as the terrorists’ headquarters. Such analysis not only glosses over the systematic institutional hypocrisy with regard to the city’s, admittedly, major problems (which are confronted with the usual mix of militarisation and social neglect) but it also mistakes such wider social unrest for the jihadi’s personal motivations. Besides the fact that Belgium still produces more foreign fighters than any other European country, one must not forget that none of the attackers (neither of Paris nor of Brussels) were interested in radical Islam until very late before they decided to dedicate themselves to the armed struggle. Observers, like Olivier Roy and Fabio Merone, who know the wider recruitment basis of ISIS in Europe a bit, all agree that the religious extremism of these young people is nothing more than anger dressed as Islam. Otherwise how do you explain that Abdelsalam Salah was “drinking beer and smoking joints” a few weeks from the attacks of the Bataclan, as some of his friends recalled in front of the cameras…

In that respect I much more preferred a report by l’Espresso (unfortunately not translated into English) which places the reasons for this rage in the socio-cultural divide between first and second generation immigrants, and the fact that immigrant youth risk to see their host country and their parents as traitors of a failed life project (or, as one foreign fighter explained to his mother shortly before he left: “If I had blond hair and be called Jacques I would most likely be sitting at my comfortable job at the commune, but with my Arab name I can’t even find work as a street-sweeper”). Even if this sounds absurd for the majority of muslim youth in Belgium, ISIS has become very apt at exploiting the projects of revenge that germinate in a life enmeshed with boredom, frustration and petty criminality for a minority of them in very similar ways as the Camorra has taken grip over its strongholds of Scampia or Castelvolturno in the Italian de-industrialized South. With the only difference that ISIS does not (just) promise money and power but also paradise. Feeling rejected by their homes, organised violence provides for these youngsters a new family in many respects -awkward as it is.

But BXL22M also forces us to consider more seriously the changing geography of global warfare these days. Besides the risk of urban conflict strategic think thanks warn for (of which Brussels has been another prominent example the last few days), global jihad cannot be limited to a war ‘in the borderlands’, but it also comprises a wider structural basis in the many de-industrialized cities of the North that continue to germinate frustration and revenge. How to connect these dots will be an important task for the future, as will be the challenge to avenge right-wing extremism that is rising at equal pace.

The Grey Zone

While a few prominent public intellectuals in Europe, like Slavoj Zizek and Bernard-Henry Levy, rather brusquely ask us to ‘get real’ about the Islamic State threat by closing territorial borders and identifying the enemy among us –a narrative that comes dangerously close to what some neoconservative pundits are promoting since some years across the Atlantic- Middle East experts confront the global public with a series of uncomfortable truths. I present three of them here.

- Scott Atran, who testified before the US Senate armed service committee and the UN Security Council, warns us not to consider ISIS as a band of mindless or nihilistic extremists, but rather take seriously their moral mission to ‘save the world’…

“… what inspires the most uncompromisingly lethal actors in the world today is not so much the Qur’an or religious teachings. It’s a thrilling cause that promises glory and esteem.”

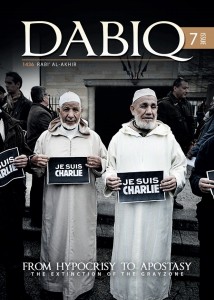

A terminology that keeps popping up in this discussion is that of the Grey Zone. Originally referring to an editorial in ISIS’s online magazine Dabiq (and not to Primo Levi’s chapter about camp life in Auschwitz –although some level of comparison would certainly be welcome here), it describes the twilight zone inhabited by Muslims worldwide, in which they are required to make a choice to live between the ‘kufra’ (infidels) or the caliphate –a choice the Paris attacks were meant to intensify. In that sense, the attacks were indeed about sovereign power, though not in the way Bernard-Henry Levy interprets it –but actually as a realm of life and death. Or, as Claudio Minca and Rory Rowan mention in their recent book where they discuss Carl Schmitt’s ideas on sovereignty and space:

A terminology that keeps popping up in this discussion is that of the Grey Zone. Originally referring to an editorial in ISIS’s online magazine Dabiq (and not to Primo Levi’s chapter about camp life in Auschwitz –although some level of comparison would certainly be welcome here), it describes the twilight zone inhabited by Muslims worldwide, in which they are required to make a choice to live between the ‘kufra’ (infidels) or the caliphate –a choice the Paris attacks were meant to intensify. In that sense, the attacks were indeed about sovereign power, though not in the way Bernard-Henry Levy interprets it –but actually as a realm of life and death. Or, as Claudio Minca and Rory Rowan mention in their recent book where they discuss Carl Schmitt’s ideas on sovereignty and space:

“Existential conflict should be understood here to indicate ‘concrete’ life and death struggles involving the potential loss of human life and not as a metaphor for some generalized concept of social conflict… [Carl] Schmitt explicitly stated that, ‘the friend, enemy, and combat concepts receive their real meaning precisely because they refer to the real possibility of physical killing’ (authors’ italics). Thus, the political is a source of meaning more fundamental than that found in other spheres of human life, since it concerns the very question of existence as such.”

- The other uncomfortable truth is that while media indeed does report about terror bombings across the world, people react emotionally to what is dear and close to them. In his in-depth analysis of the Paris-Beirut comparison, which is brought up continuously to evoke disparate global concern (and make people feel guilty about it), Vox journalist Max Fisher quotes tweeter Jamiles Lartley who says, quite succinctly, I think: “people should be permitted to grieve and seek redress for specific violence and suffer without being redirected or corrected.” Instead Fisher presents the more complicated question what causes disproportionate care and concern for one country over another in terms of grief and daily struggles (not in the least in hosting the refugee populations that are driven away exactly by the conflicts Western public intellectuals are avoiding in their analysis: in this context I remember an El Pais cartoon some time back saying ‘we are fleeing the wars that once were yours’…). Clearly ‘the media’ is too easy a villain to accuse the lack of global empathy here…

- The most uncomfortable truth of all is presented to us by Nafeez Mossadeq Ahmed on Open Democracy: that of the regional geopolitics that continue to feed ISIS. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the UAE, Kuwait and Turkey –all key Western allies– played lead roles in funnelling support to ISIS precursor Al Qaeda. And Turkey sponsors ISIS both through direct military cooperation and through actively facilitating ISIS black market oil sales.

“ISIS, in other words, is state-sponsored –indeed sponsored by purportedly Western-friendly regimes in the Muslim world who are [also, paradoxically] integral to the anti-ISIS coalition.”

Safeguarding the grey zone, Ahmed -but also Etienne Balibar adds, thus not only requires Western publics to hold their governments accountable for such foreign policy mischiefs but it also means actively rejecting exactly the type of band-wagoning Levy and Zizek appear to propose:

“… safeguarding the “grey zone” means more than bandying about the word ‘solidarity’ – it means enacting citizen-solidarity by firmly rejecting efforts by both ISIS and the far-right to exploit terrorism as a way to transform our societies into militarized police-states where dissent is demonized, the Other is feared, and mutual paranoia is the name of the game. That, in turn, means working together to advance and innovate the institutions, checks and balances, and accountability necessary to maintain and improve the framework of free, open and diverse societies.”

p.s. after days of frenetic searching across hospitals, a friend of a Parisian friend who went missing the nigth of the attacks has finally been found… death. I mourn her loss –not for any particular reason, but because she is a human being. I hope that is still permitted.

Global ban-lieu?

The many predictions. The fear. The waiting. And then, the blast.

It is ironic that among the victims of the Paris Attacks last Friday, there was a volunteer of the humanitarian aid organization Emergency, whose members operate in Syria and Afghanistan to assist victims of war. Commenting her death, Gino Strada, the founder of Emergency, summarized this irony by paraphrasing the German poet Bertold Brecht:

“The war that comes is not the first one. Before there have been other wars. At the end of the previous one there were winners and losers. Among the losers the poor people were hungry. Among the winners the poor people were equally hungry.”

Years of destruction and “strategic foreign policy blunders” –starting with the ill-conceived transition of post-Saddam Iraq and continuing with a series of haphazardly planned interventions in North Africa and the Middle East led by an axis of French, British and US forces, are presenting their bloody bill to populations in Syria, in Iraq, in Turkey, in Libya and Lebanon…

–and now, also, in Europe.

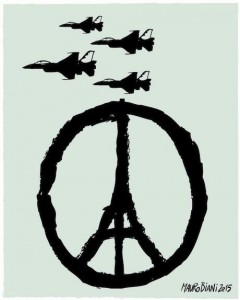

-Paris

Even more so than the previous one in January, the Paris attack of 13 November shows that there can be no more far-away wars for Europeans. After 50 years of relative ‘peace’, which was, in hindsight, no less hard-lived than it was illusory and fragile, the Old Continent is once more caught in the eye of the storm. That in itself may already be a rather hard lesson to swallow for some of its inhabitants: as intelligence services across the Atlantic are warning more attacks may be coming ahead soon, we might actually be seeing the first war refugees moving across Europe as a result of persistent terror threats in some countries (one friend of mine, who lives at 200 meters from one of the attack sites, admitted she had wanted to leave France for some time: ‘you can literally feel the tension in the streets,’ she said. I imagine she is not the only one).

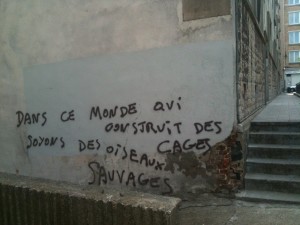

A second fundamental insight, I think, is that Europe is increasingly waging a war on itself. By this I mean not only the eroding rights of secondary and aspiring citizens who are living their increasing ly secluded lives. But also the very idea of unity in diversity –one of the fundamental values the European project and the ‘no-more-war’ credo it once pretended to stand for, is falling flat on its face. In that sense, the contrast between the mixture of nationals sipping their drinks before gracelessly being gunned to the ground by ISIS attackers at the Carillon and Petit Cambodge bar and restaurant last Friday, and the recruiting grounds of ISIS/ISIL/Daesh a few miles away from there in the Parisian banlieus (‘banned spaces’) and in the Belgian communes of Molenbeek and Verviers could not have been more telling. Has ‘the problem of the banlieu’ –as one bourgeois gallery owner loathingly uttered in the movie La Haine after the 2005 riots gone global? Ironically, 2005 was the second time France declared a state of emergency after the Algerian war of independence, but not on a national-wide scale. After the Paris attacks, President Francois Hollande felt the need to do so once more.

ly secluded lives. But also the very idea of unity in diversity –one of the fundamental values the European project and the ‘no-more-war’ credo it once pretended to stand for, is falling flat on its face. In that sense, the contrast between the mixture of nationals sipping their drinks before gracelessly being gunned to the ground by ISIS attackers at the Carillon and Petit Cambodge bar and restaurant last Friday, and the recruiting grounds of ISIS/ISIL/Daesh a few miles away from there in the Parisian banlieus (‘banned spaces’) and in the Belgian communes of Molenbeek and Verviers could not have been more telling. Has ‘the problem of the banlieu’ –as one bourgeois gallery owner loathingly uttered in the movie La Haine after the 2005 riots gone global? Ironically, 2005 was the second time France declared a state of emergency after the Algerian war of independence, but not on a national-wide scale. After the Paris attacks, President Francois Hollande felt the need to do so once more.

la Borne ‘labyrinth’

Molenbeek

We must not forget that what are now derogatively called the continent’s seething ghetto’s and hotbeds of criminal marginality have grown to be like that as a result of decades of conscious neglect, marginalization and erosive welfare politics –which at once hardened marginalization while sidestepping the much more difficult task of proper integration -and not just in run-down city neighbourhoods (on this note, see Mustafa Dikec‘s Badlands of the Republic but also, in slight contrast, this paper on Sharia4Belgium by Belgian politologist Rik Coolsaet). The social background of European fundamentalist militants may be another clear sign that at bottom’s length, this war has very little to do with religious values a priori and more with ways to avenge broken dignity: from Nizar Trabelsi to Ibrahim Abdeslam, most European radical Muslim fighters have followed a trepid path of petty crime only to become radicalized after conscious brainwashing and training by a carefully managed collective of military / ideological instigators. Reason why, according to some authors, it might actually be better to compare the organization’s culture to a mafia or organized crime group –a form of de facto power governing a segment of the globe’s borderlands -according to Loretta Napoleoni.

Whatever ISIS/ISIL/Daesh’s future terror strategy might become in terms of instrumentalizing that contrasting reality between Europe’s ‘infidels’ & ‘liberators’, the ‘free’ and ‘unfree’ world, the effects of this attack will likely have an incisive role in the life of European citizens and their rights for years to come. As the fear sets in, harnesses are put on, and knives are being sharpened –needless to say who the losers of that struggle will once more be.

Military migration control

In line with previous reporting by The Guardian and other news outlets, Wikileaks just released a classified EU plan for a military operation against people smuggling networks and infrastructure in the Mediterranean, including the destruction of docked boats and operations within Libya’s territorial boundaries.

War connects places

While anti-terror operations in Europe go on unabated (for example this morning, several Chechen terrorists were arrested in Southern France) the critique against some of the Western posturing is also rising. Mustafa Dikeç, who I mentioned in my post, writes this brilliant reflection from Paris, France.

The appeal of fundamentalist discourse resides in its potential to turn a feeling of powerlessness into one of being all too powerful, guided by a divine source and a heavenly objective (…). If there is an element of truth in this observation, if the fundamentalists do indeed capitalise on the imposed inferiority of discriminated youth and provide them with doctrines and fora designed to make them feel somewhat powerful, then the French state has been doing exactly the opposite – not just in terms of concrete policies, but also by the deployment of stigmatising language by its high-ranking officials that went unsanctioned.

This attitude, together with Charlie Hebdo’ insistent irreverent style, is now causing more trouble in Africa and Asia. Two days of riots in Niger’s capital Niamey has left half a dozen deaths and many churches burnt. The riots occurred as a reaction of the president’s participation in a mass manifestation days after the gun attacks against Charlie Hebdo. Chechnya’s capital Grozny has known some of the most violent protests since the cooling down of the protracted civil war there; these riots -which were, interestingly, named ‘islamic protests’ by the Washington Times– arise along with manifestations in Jalabad and Kabul. Indeed, war connects places, Duffield wrote back in 2007:

While the recent terrorist attacks on America have had a profound social and political impact, it would be wrong to suggest that they mark a wholly new or unexpected departure. What we are witnessing is a significant consolidation of systems and inter-connections that have been slowly maturing for several decades. The violence of 11th September was an historic moment that quickly pulled together many existing threads to reveal a fuller sense of the design. It is now easier to appreciate the consolidation of a new security terrain shaped by the advent of ‘network war’. Like the Cold War before it, network war now defines the global predicament. Across this contested landscape, bounded by the opportunities and threats afforded by globalisation, new forms of autonomy, resistance and organised violence engage equally singular systems of international regulation, humanitarian intervention and social reconstruction. Increasingly, what one could call the ‘them’ and ‘us’ components of this new security terrain, that is, those systems of resistance and their opposing forces of regulation and intervention, have to varying degrees both assumed a networked and non-territorial appearance. While states and their security apparatuses remain pivotal, in both camps they situate themselves within and operate through complex governance networks composed of non-state and private actors.

‘Us’ against ‘Them’

Given my experience with armed conflict, people have been asking my opinion about the terror attacks and anti-terror operations in Paris and Belgium. Despite the rhetorical proliferation around this issue, I add two small reflections. I could summarise them in these two, very short statements:

1. ‘we are them’ –or the collapsing scale of global military engagement in the (post?)-War on Terror age.

2. ‘they are (like) us’ –or the paradox of an emerging global society

Oranges for Rojava

Ya Basta! Bologna – Sos Rosarno – Alchemilla GAS Bologna organize a solidarity event for Rojava and SOS Rosarno on 23 January.

Ya Basta! Bologna – Sos Rosarno – Alchemilla GAS Bologna organize a solidarity event for Rojava and SOS Rosarno on 23 January.

The fight against the mafia, labor exploitation, and racism meets the battle for self-determination and democracy.

As part of the national campaign Rojava Calling, the sale of oranges from SOS Rosarno and a Kurdish dinner support the front of women and men engaged in rejecting totalitarianism and the supremacy of ISIS, to defend an idea of plural and secular society.

You may subscribe here.