I am glad to announce the appearance of the paperback version of my book Violent Capitalism and Hybrid Identity in the Eastern Congo with Cambridge University Press. The book comes at a time of great turmoil in Congo’s north-east, where the end of armed conflict is not at all in sight, as recent reports from Ituri and le Grand Nord reveal. Reading through the detailed colonial and postcolonial history of this region makes one aware of the underlying dynamics of this armed conflict, which finds its origins in a series of intricate relations between regional politics, cross-border economies and capital accumulation. As Janosch Kullenberg writes in a recent review: the book moves beyond the “stereotypical and simplistic understandings about state failure and chronic violence in central Africa [which] have not led to great insights about either the mechanisms at work, or the emerging orders.” Instead the recent reports about continued violence in Eastern Congo make it worthwhile to approach this “constant crisis” through the long-term consequences of every day decision-making through a “ethnography of critical life worlds”.

Category Archives: postcolonialism

Workshop Impressions

In the meantime, the first impressions of our Brussels workshop have been posted online by our funders… Thank you all for a very rewarding experience.

New Plantation

With less than one month to go, I gladly announce here the closing event of the New Plantations project, in Brussels on 14 December. For the last two years our international research team from Switzerland, Belgium and Italy has analyzed migrant work conditions in Europe, focusing on dynamics of illegalization, racialization and labour exploitation in the contintent’s agricultural sector.

Directed by a group of activists, artists and academics, the event will highlight the forces at play in the European horticultural industry. Rather than a classic presentation-based conference, the workshop will be pinpointed around several interactive tables, each of which will address a specific theme. The event will be closed by a short theatre show by Cantieri Meticci, whose members have been active participants in this project.

Anyone who is interested in participating, please send a confirmation email to project director Timothy Raeymaekers (timothy.raeymaekers@geo.uzh.ch) by November 30th. More information on time, place and logistics of the event can be found on our facebook page and on the attached flyer. The language of the event will be French.

https://snis.ch/project/new-plantations-migrant-mobility-illegality-racialisation/

Oro Rosso, Sangue Nero

Invitation to the the first episode of a series of sessions on the Black Mediterranean – a topic amply discussed on these pages.

location: the MET – Bologna,

time: March 25, at 16.30-23.00,

During the meeting we will discuss the working conditions of Black African labourers in South Italy’s tomato fields (particularly Puglia and Basilicata). The workshop will revolve around several tables, each of which will produce a different map of this agricultural frontier.

Tre Titoli

In passing, I mention this art movie produced by Nico Angiuli, winner of the arts and human rights competition for young artists and cultural institutions curated by Connecting Cultures and Fondazione Ismu, which is on display in Rome’s Quadriennale’s exhibition.

The project involves the Tre Titoli hamlet, nearby Cerignola, in Southern Italy’s Puglia Region. It narrates the symbolic intersection of the Ghanese community, which over the last decades has occupied some of the abandoned houses left after the hamlet’s faltered agricultural reform of the 1950’s and 70s, with that of the rural proletarian struggle led by union leader Giuseppe Di Vittorio during that very period.

Aware of these dire conditions, the artist aims at abandoning the usual two-dimensional representation of this African ghetto in the media by introducing practices of self-narration, in order to allow for a more complex scenario of compromise and tension, and thus giving voice to spontaneous micro-processes of resistance against widespread attempts to normalize this marginalisation process of local voices.

The project has been realised in collaboration with Terra Piatta (or ‘Flat Land‘), a program of research and artistic, social and cultural production, curated by Vessel, a cultural platform in Lucera, Puglia, with a specific focus on artistic practices in dialogue within a rapidly changing rural context.

https://youtu.be/CpVFKubnHn4

Meticciato

On the Problematic Nature of a Word

by Camilla Hawthorne and Pina Piccolo

I am happy to act as a host for this joint article by Camilla Hawthorne and Pina Piccolo on the politics of ‘mesticcatio’, or cultural hybridity, in Italy. Since their essay Anti-racism without race in the journal Africa is a Country, a number of developments spurred them to deepen this initial discussion, which was prompted by the racially motivated killing of Nigerian refugee seeker on Emmanuel Chidi Nnamdi in Fermo, Italy, in July 2016.

In their current contribution, which appeared originally in Italian on the la macchina sognante blog, they expand on some of the issues currently facing the anti-racism movement in Italy. Their joint joint contribution seeks to draw both from their professional research and personal experiences in the anti-racism and immigrant movements in Italy and the US.

Israel’s Eritreans in the Picture

Check out the Guardian Africa Network photo album today with pictures of Eritrean migrants celebrating mass and baptising their children in Tel Aviv, Israel. The improvised suburban spaces used for these celebrations not only provide a spiritual escape from often aggressive government immigration policies but also recreate a sense of ‘home’ in a politically hostile environment. To place this in wider context, interesting work is currently presented on the plight of African refugees in Israel nowadays, amongst others by Haim Yacobi, Barak Kalir and Laurie Lijnders.  Particularly Yacobi’s discussion of the ‘Villa in the Jungle’ – a trope that highlights Israel’s moral geographic engagement with Africa, significantly informs this debate. ‘Walling off’ Eritrean refugees, he says, has not exclusively become a vector for reproducing Israel identity as set apart from Africa and the Middle East, but also reflects the persistent attempts of government authorities at active demographic engineering and urban segregation. The active exclusion of Eritrean churches thus has to be read in this context, of the racialisation of political space that characterises Israeli society as a whole.

Particularly Yacobi’s discussion of the ‘Villa in the Jungle’ – a trope that highlights Israel’s moral geographic engagement with Africa, significantly informs this debate. ‘Walling off’ Eritrean refugees, he says, has not exclusively become a vector for reproducing Israel identity as set apart from Africa and the Middle East, but also reflects the persistent attempts of government authorities at active demographic engineering and urban segregation. The active exclusion of Eritrean churches thus has to be read in this context, of the racialisation of political space that characterises Israeli society as a whole.

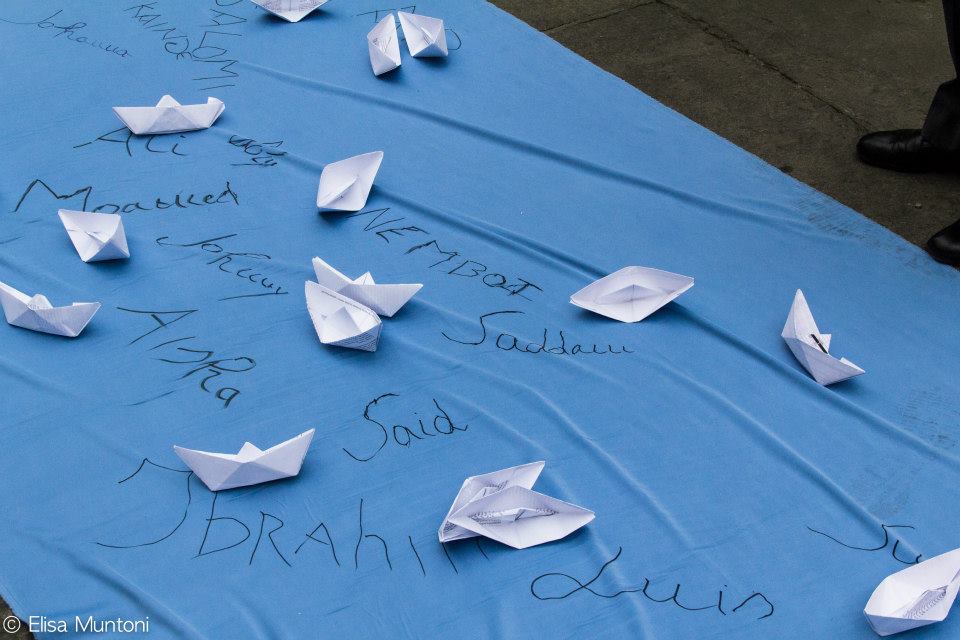

The colour line

Further to my earlier comment a few weeks ago, which critically assessed Matteo Renzi‘s personification of people smugglers in Libya as the slave drivers of the twenty-first century, I to add two fresh posts that further explore the reasoning behind Europe’s bordering business. On Africa is Country, Enrique Martino interestingly writes how representing people on the move as easy prey for unspecified bands of ruthless traffickers is also a colonial script, because it portrays migrants as ignorant and passive. But their itineraries are also driven by an imperialist history of white people moving deep into the African continent.

And yesterday, opendemocracy.net published a letter signed by 300 slavery and migration scholars, which criticises the EU’s unfolding naval campaign against ‘human traffickers’ in the Mediterranean along the same lines:

[Comparing human traffickers to the slave traders of the 21st century] is patently false and entirely self-serving. (…) [W]hat is happening in the Mediterranean today does not even remotely resemble the transatlantic slave trade. Enslaved Africans did not want to move. They were held in dungeons before being shackled and loaded onto ships. They had to be prevented from choosing suicide over forcible transportation. That transportation led to a single and utterly appalling outcome—slavery.

As I also wrote in the same post, human rights abuses rather occur in the many outsourced host and detention centres, where migrants risk to wither away in oblivion, or worse, are subjected to violence and torture (as has been the case in Libya, but also in Germany and Italy, as of lately).

In two additional posts, Nick De Genova and Harald Bauder reiterate that there is fact nothing natural about migrant’s illegality, but that their illegalization entails an active process of denied protection, involving often intensified efforts to increase migrant’s vulnerability. In other words, governments are complicit in the strategy to deny rights to migrants, resulting in a self-fulfilling spectacle of the border that excludes them from participating in the economies they sustain with their very lives.

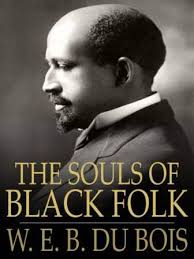

As if by accident, Sandro Mezzadra’s public lecture on W.E.B. Du Bois‘ concept of the colour line -a lecture he gave at the annual KritNet conference on Borders, Migration -and Race, was just published online on Voice Republic along with the interventions from Juliane Karakayali and Vassilis Tsianos, Patrizia Putschert and Klen Nghi Ha.

There is a need to broaden the geographical, conceptual debate on the migratory regimes ‘in the crisis’…

Interesting terms that turn up in Mezzadra’s speech are the verticality and the temporality of the border (picking up on the work of Vicki Squire, Robert Latham and others), and the colour line…

The paradox of territory

In Italy, quite a number of occupied buildings I previously indicated – inspired by Heather Merrill – as ‘black spaces’ (the shelters, detention centres, condemned urban buildings, and other locations representing those who, by virtue of their asylum status and association with African territories, are rendered non-citizens, even though they are an integral part of modern Western societies and the economies that sustain them) are currently threatened with eviction.

In Turin, the occupants of exMOI, 750 refugees from 26 different African countries (apparently including 15% are women and 30 children) have been ordered to pack and leave. During their March last Saturday, they carried huge banners depicting their Black mediterranean presence.

In Rome, the occupants of Palazzo Salaam (an estimated 1.200 refugees and beneficiaries of humanitarian protection, mostly from the African Horn) loose their residence permit as a result of the new housing legislation proposed by the Matteo Renzi government.

In Bologna, 200 families occupying exTELECOM, a building opposite the new city council, are threatened with eviction.

Given the chronic shortage of places to host refugees and asylum seekers across the country, UNHCR and Medici per i Diritti Umani, a medical charity, estimate, thousands of asylum seekers and beneficiaries of international protection are living in precarious housing conditions. For example in Turin, a local migrant association estimates that around 600 refugees and people benefiting from a humanitarian protection status live across 7 occupied buildings in the city. Considering other such ‘black places’ in Bologna, Rome, and Florence in this calculation, the numbers easily add up. This number does not even include the homeless refugees whom, as one Malian who fled to Germany explained, are sleeping under the bridges of Italy’s metropoles.

The paradox lies precisely in the new housing legislation (or ‘piano casa’) that was voted in 2014 but is being put into practice only recently. Article 5 of this plan says: “Whoever occupies a property illegally without title cannot apply for a residence nor for a connection to public services in relation to this property, and [by consequence] all acts in violation of this prohibition shall be declared null in front of the law.” The converted law (voted in March 2014) is even more severe: “Those who illegally occupy residential public housing cannot participate in the procedures fro obtaining housing for five years following the ascertained date of the illegal occupation.”

Besides the curious liaison between residential property and public space in this legislative measure (residential public housing), the concrete application of it means that whomever occupies a building of black of better alternatives, can be denied official residency. This poses a source of anxiety particularly for the refugees and asylum seekers whom since the Nord Africa Emergency of 2012-2013 have been thrown out in the streets for a lack of assistance by the (theoretically) protecting state.

The comment by Antonio Mugolo, president of Avvocati di Strada, an association that takes up the defence of homeless people in Italy, is telling in this respect: “Without residence,” reminds Mumolo, “you cannot vote, you cannot cure yourself, you cannot receive a pension nor benefit from local welfare, you cannot obtain formal employment, you are not entitled to legal assistance … [In short] taking away the residence permit from people who occupy a building literally means placing those people outside of society, making them invisible, erasing in one single shot the possibility to confront their difficulties… It is remarkable that a plan, which should help families to confront the crisis, precisely bears these consequences,” he concludes.

Somehow this situation reminded me of the inherent violence expressed in the term state territory. So whereas, on the one hand, as Stuart Elden would say, territory is a political technology to measure land and control terrain, territory is also the effect, the product of spatially fixing relational networks into this bounded space. Close to Michael Watts‘ and David Delaney‘s reading, the legislative measures I briefly illustrated above indeed illustrate the consciously violent (or ‘terrorising’?) work of territory, which, besides its calculative techniques, of marking, bordering and categorizing political space, also involves the material imposition of sovereign political power through such fixed spatial units. Citizens and non-citizens alike thus find themselves frequently caught in the deadlock of territory as it provides no alternative space for making a life and developing a livelihood outside of its constraining perimeters. With sometimes paradoxical results.

courtesy Nick Hannes

Follow the Tomato!

Following my earlier post on the racial geography of the Black Mediterranean, colleagues keep pointing me at North-South connections in agri-food commodity chains, particularly with regard to tomatoes. My colleague Christian Berndt, for example, has written this wonderful comparison between the EU/North Africa and US/Mexico borderlands together with Marc Boeckler (click here for pdf and here for a link to the edited book chapter). They adopt a consciously marginal perspective – a view from the border – to document the heterogeneous associations that literally connect the agricultural fields to the supermarket shelves.

Following my earlier post on the racial geography of the Black Mediterranean, colleagues keep pointing me at North-South connections in agri-food commodity chains, particularly with regard to tomatoes. My colleague Christian Berndt, for example, has written this wonderful comparison between the EU/North Africa and US/Mexico borderlands together with Marc Boeckler (click here for pdf and here for a link to the edited book chapter). They adopt a consciously marginal perspective – a view from the border – to document the heterogeneous associations that literally connect the agricultural fields to the supermarket shelves.

“In tracing the network tomato we posed one central question: How is the tomato held stable as a tomato while it is not only displaced through space but also subject to multiple ways of b/ordering that try to control the double play of framing and overflowing?”

The authors interestingly conclude with a quote form Ulrich Beck: “It is not the dissolution of borders, but rather border negotiation and border work which is at the heart of current globalisation processes.”

Their approach reminded me of the original approach taken for example by Ian Cook et al. (Follow the Papaya). As Cook writes while following his papaya from the field to the plane, to the London supermarket, and to the fruit bowl:

Although the narrative appears linear, it is not, as cross-cutting connections are drawn among and outside its constitutive stages: to colonialism, to the World Trade Organization (WTO), to Western middle-class consumption aesthetics, to the diseases and pests of exotic fruits, to the character of international air cargo transportation, and to developing-world labour control and surveillance. This is an unbounded, dense network of associations. And precisely because it isn’t a simple chain, the commodity itself is no ‘trivial thing’; it is composite, defetishized, decrypted, reflecting all manner of trace effects.

Years ago I remember seeing this Brazilian documentary that followed a tomato from the field -where it grows, is watered, taken care off, and then, as it is further transported, sold and carried home, it ends up in the garbage of one wealthy family in Rio de Janeiro (unfortunately I cannot find the documentary any more, if anyone can give me a hint that would be highly appreciated).

A friend journalist then mentioned this feature on the Dark Side of the Italian Tomato by Mathilde Auvillain and Stefano Liberti.

“Makola market, the main market in Accra – one of the largest in Western Africa – is the commercial heart of the capital (…) Everywhere, wooden stalls seem to be laden down by red tins of tomatoes, skilfully balanced by the sellers in mysterious geometric formations. (…) “Salsa”, “Fiorini”, the brands are Italian pastes (…) even the Chinese product “Gino” displays the Italian tricolour on the tin to attract customers.”

“(…) the government should have limited the quantity of tomato paste coming in from abroad. “If the market had been regulated, the farmers would’ve gotten better prices and would’ve had a market for their produce. But the government did the exact opposite. It swung open the doors of the country to imports of European tomato paste. Now there’s such a wide choice and such an amount of produce that it’s practically impossible to sell locally-grown tomatoes”.

The webdoc concentrates amongst others on the swamping of African markets by European and Chinese tomato paste. What I didn’t know is that many of the African day labourers who end up picking tomatoes in Southern Europe come from tomato growing regions themselves; as a result of commercial dumping, these producers often have no other choice than to re-enter the commodity chain as unfree labourers. Bernard Hazard already mentioned Béguédo in Burkina Faso. The documentary by Mathilde Auvillain and Stefano Liberti furthermore mentions Upper east Region in Ghana. This raises the further question how African seasonal workers are recruited, how their labour force figures in a wider restructuration of agri-commodity chains dominated by big retail businesses, and how informal employment schemes intermingle with formal border regulations.

Finally last week, I became acquainted with an alternative way of organizing local tomato productions during a fair organised by SOS Rosarno. With their help, a group of African producers from Venosa, Basilicata, proposed their product, bottled tomato sauce, which says ‘free from labour exploitation’. Labourers are regularly employed without the intervention of criminal intermediaries, or caporali.