Lots of news on asylum in Europe these days…

While European and African leaders are trying to hammer home an agreement in Malta, including a €1.8bn “trust fund” in an attempt to cajole African governments into taking migrants back and stopping them from leaving the continent in the first place, Europe’s individual states are toughening their stance. Sweden, once considered the haven of social democratic welfare and migrant rights, has announced the introduction of temporary border checks. The controls will come into effect from midday local time on Thursday and will last initially for 10 days, the BBC writes.

In the meantime, German chancellor Angela Merkel feels increasingly battered at home and abroad for lack of vision, and for her unwillingness to apply tougher measures. With Schengen in shatters, the European dream has clearly vanished, the European commissioner for immigration, Dimitris Avramopoulos, said. In the meantime, a report from the Brussels based Migration Policy Institute lays bare the huge discrepancies between national immigration procedures. Reception conditions vary greatly from country to country, with some offering the minimum standard of shelter, food and clothes (like Italy and Greece) and others offering services for active integration, including schooling and work permits -which causes migrants to ‘shop around’ for better benefits.

The biggest obstacle, however, appears to be working permits: because European directives only designate the right to work, but not the actual possibility to exercise this right, migrants are sometimes actively pushed back into illegality. Similar perplexities surround the right to housing, on which I’ve written before here: without actual residence permits, migrants are regularly excluded from fundamental rights to health care and other social services, regardless of their paperwork. As long as these rights are not properly defined within a revised Dublin system -which has in any case become ‘obsolete‘ according to Angela Merkel, the European right to asylum will remain largely death letter.

While the European asylum system is disintegrating, photographer Giles Duley reports back from Lesbos as part of his work with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). He introduces a new series of images documenting the plight of the world’s displaced people: cemetery of souls indeed…

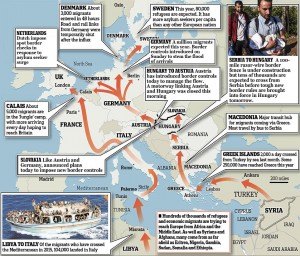

migrant flows across the Balkan route are triggering an intriguing sequence of openings and closures towards the EU, as this interesting map from

migrant flows across the Balkan route are triggering an intriguing sequence of openings and closures towards the EU, as this interesting map from