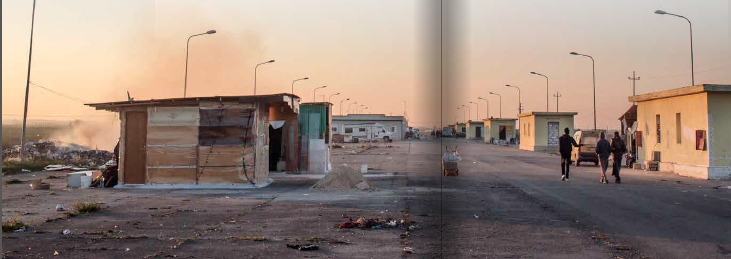

The Grand Ghetto is no more… On Thursday night, a fire destroyed the remains of Italy’s biggest informal labour slums, only hours after police had moved in to forcefully evict its 3-400 residents. The Grand Ghetto, between Foggia and San Severo (Puglia), is located in one of Italy’s prime agro-food basins, the Capitanata, which produces about one third of the country’s industrial tomatoes (the famous pellati). Since the mid-1990s it has grown into a permanent settlement, hosting between 300 and 3.000, mostly West African workers.

Recently, the ghetto had become a thorn in the eye of Puglia’s regional governor Michele Emiliano, who is running as president of the social democratic party. After several failed attempts to dislodge its inhabitants in the last half decade, his administration has worked hard to find alternative living and working conditions in the area with the assistance of several community organisations. One of these is called Casa Sankara, an association directed by two former day labourers Herve Papa Latyr Faye and Mbaye Ndiaye, from Senegal, who currently manage the Fortore enterprise on the SS16 from Foggia to San Severo, and currently hosts about a 100 immigrants. But while police were putting ghetto residents on buses to transport them to Casa Sankara and other locations (including, for some, police headquarters) on Wednesday, about a hundred workers are believed to be dispersed in the area, sleeping rough and occupying abandoned buildings. This number will likely increase at the start of the tomato season late March, when about 30.000 agricultural workers join the area to work as day contractors -usually without legal pay and under the close supervision of criminal intermediaries (so-called caporali).

Several questions are raised now as to the efficacy of the anti-ghetto operation. First, the rapidity of the intervention has, unwillingly, caused a number of victims. While fire workers worked hard to quench the flames on Thursday, unfortunately help came too late for two Malian citizens, Mamadou Konate (33) and Nouhou Doumbia (36), whose bodies were found carbonised in one of the destroyed barracks. Apparently one of them, Nouhou, was deaf, and could not hear the blazing fire approaching his shack. The other victim, Mamadou, was an active member of a local association which had denounced labour exploitation on several occasions. Ghetto residents publicly ask themselves how this tragedy could happen under the eye of state security forces, who were massively present during the eviction.

Several questions are raised now as to the efficacy of the anti-ghetto operation. First, the rapidity of the intervention has, unwillingly, caused a number of victims. While fire workers worked hard to quench the flames on Thursday, unfortunately help came too late for two Malian citizens, Mamadou Konate (33) and Nouhou Doumbia (36), whose bodies were found carbonised in one of the destroyed barracks. Apparently one of them, Nouhou, was deaf, and could not hear the blazing fire approaching his shack. The other victim, Mamadou, was an active member of a local association which had denounced labour exploitation on several occasions. Ghetto residents publicly ask themselves how this tragedy could happen under the eye of state security forces, who were massively present during the eviction.

Secondly, people are asking what will become of the shop owners, cooks, prostitutes, and other residents who have been dislodged by the operation. During a protest march organised on Wednesday -closely monitored by some African caporali, according to witnesses- about a hundred ghettisards showed billboards saying ‘we want to live in the ghetto’. Clearly, the prospect of being hosted in one of the region’s reception centres looks largely unattractive to the majority of former ghetto residents who come to Puglia to work. At the same time, the protest also shows to what extent foreign workers, who often depend closely on intermediaries for their residence status, are systematically marginalised and segregated.

Finally, questions arise around the judicial investigation by the regional anti-mafia authorities (DDA), which previously sequestered the Grand Ghetto area with the ‘faculty of use’ -a privilege that has now been revoked, apparently. With only one arrest so far (of an Italian who apparently has no links to the criminal caporale system), criminal activities – including prostitution, stolen cars sales and, last but not least, illegal labour mediation – have remained undisturbed by recent operations. Yesterday, a drive-by shooting took place just opposite the hotel which hosts several police personnel engaged in the anti-ghetto operation. The shooting took place days after the mayor of San Severo decided to engage in a hunger strike, demanding more police to combat local crime. After these clear warnings, the Interior Ministry has decided to increase its presence in the area and organise a more permanent police backup.

Several questions are raised now as to the efficacy of the anti-ghetto operation. First, the rapidity of the intervention has, unwillingly, caused a number of victims. While fire workers worked hard to quench the flames on Thursday, unfortunately help came too late for two Malian citizens,

Several questions are raised now as to the efficacy of the anti-ghetto operation. First, the rapidity of the intervention has, unwillingly, caused a number of victims. While fire workers worked hard to quench the flames on Thursday, unfortunately help came too late for two Malian citizens,