In Italy, quite a number of occupied buildings I previously indicated – inspired by Heather Merrill – as ‘black spaces’ (the shelters, detention centres, condemned urban buildings, and other locations representing those who, by virtue of their asylum status and association with African territories, are rendered non-citizens, even though they are an integral part of modern Western societies and the economies that sustain them) are currently threatened with eviction.

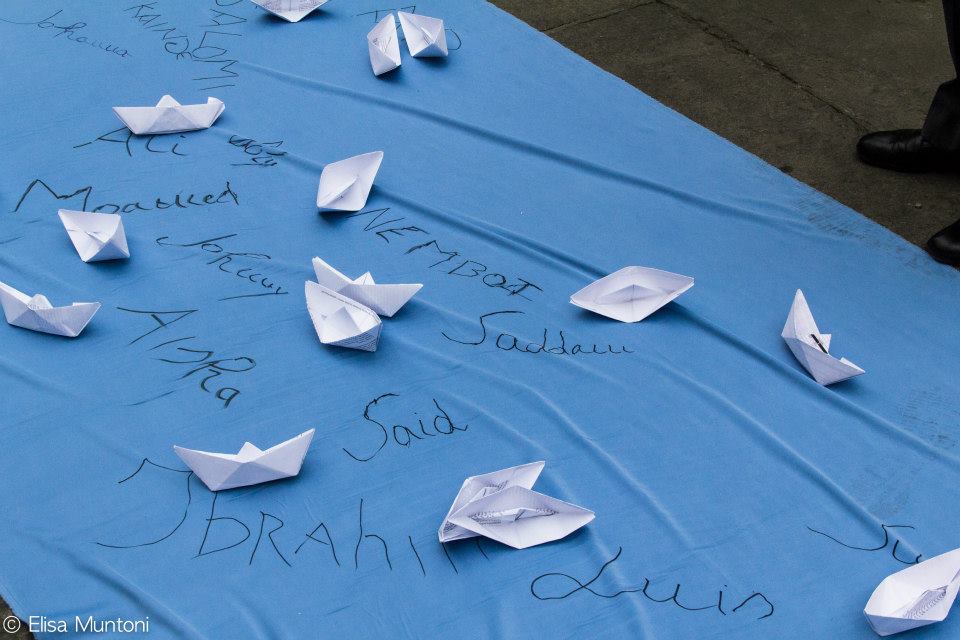

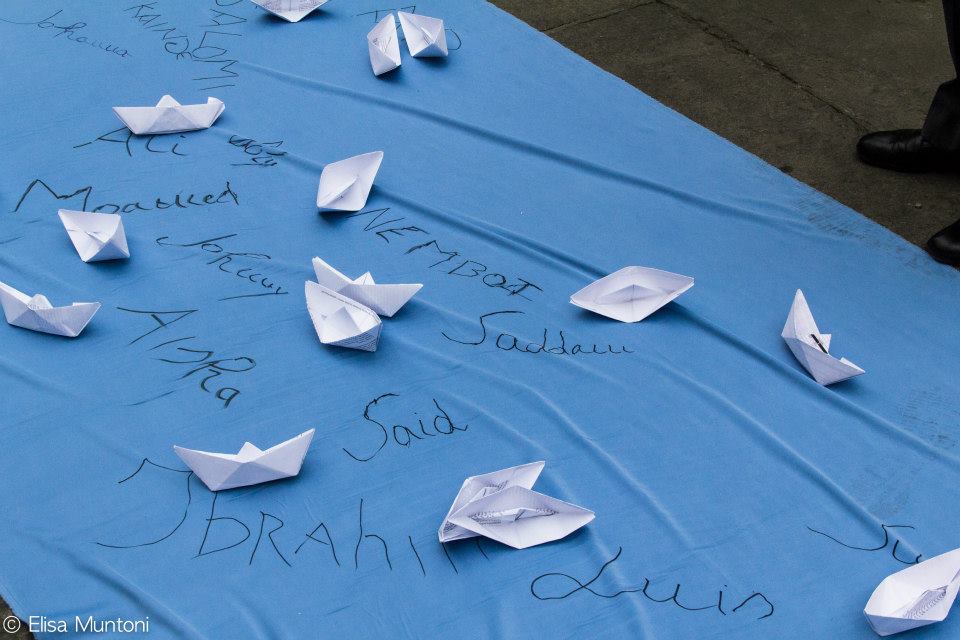

In Turin, the occupants of exMOI, 750 refugees from 26 different African countries (apparently including 15% are women and 30 children) have been ordered to pack and leave. During their March last Saturday, they carried huge banners depicting their Black mediterranean presence.

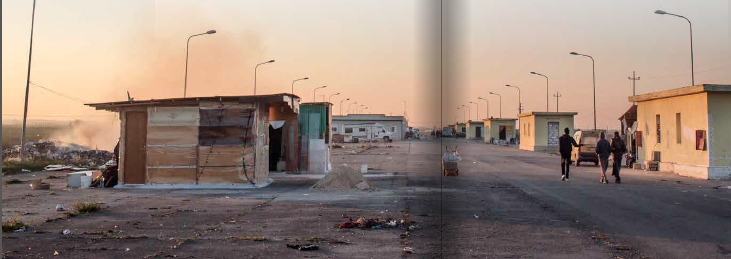

protests against evictions from exMOI

In Rome, the occupants of Palazzo Salaam (an estimated 1.200 refugees and beneficiaries of humanitarian protection, mostly from the African Horn) loose their residence permit as a result of the new housing legislation proposed by the Matteo Renzi government.

In Bologna, 200 families occupying exTELECOM, a building opposite the new city council, are threatened with eviction.

Given the chronic shortage of places to host refugees and asylum seekers across the country, UNHCR and Medici per i Diritti Umani, a medical charity, estimate, thousands of asylum seekers and beneficiaries of international protection are living in precarious housing conditions. For example in Turin, a local migrant association estimates that around 600 refugees and people benefiting from a humanitarian protection status live across 7 occupied buildings in the city. Considering other such ‘black places’ in Bologna, Rome, and Florence in this calculation, the numbers easily add up. This number does not even include the homeless refugees whom, as one Malian who fled to Germany explained, are sleeping under the bridges of Italy’s metropoles.

The paradox lies precisely in the new housing legislation (or ‘piano casa’) that was voted in 2014 but is being put into practice only recently. Article 5 of this plan says: “Whoever occupies a property illegally without title cannot apply for a residence nor for a connection to public services in relation to this property, and [by consequence] all acts in violation of this prohibition shall be declared null in front of the law.” The converted law (voted in March 2014) is even more severe: “Those who illegally occupy residential public housing cannot participate in the procedures fro obtaining housing for five years following the ascertained date of the illegal occupation.”

Besides the curious liaison between residential property and public space in this legislative measure (residential public housing), the concrete application of it means that whomever occupies a building of black of better alternatives, can be denied official residency. This poses a source of anxiety particularly for the refugees and asylum seekers whom since the Nord Africa Emergency of 2012-2013 have been thrown out in the streets for a lack of assistance by the (theoretically) protecting state.

The comment by Antonio Mugolo, president of Avvocati di Strada, an association that takes up the defence of homeless people in Italy, is telling in this respect: “Without residence,” reminds Mumolo, “you cannot vote, you cannot cure yourself, you cannot receive a pension nor benefit from local welfare, you cannot obtain formal employment, you are not entitled to legal assistance … [In short] taking away the residence permit from people who occupy a building literally means placing those people outside of society, making them invisible, erasing in one single shot the possibility to confront their difficulties… It is remarkable that a plan, which should help families to confront the crisis, precisely bears these consequences,” he concludes.

Somehow this situation reminded me of the inherent violence expressed in the term state territory. So whereas, on the one hand, as Stuart Elden would say, territory is a political technology to measure land and control terrain, territory is also the effect, the product of spatially fixing relational networks into this bounded space. Close to Michael Watts‘ and David Delaney‘s reading, the legislative measures I briefly illustrated above indeed illustrate the consciously violent (or ‘terrorising’?) work of territory, which, besides its calculative techniques, of marking, bordering and categorizing political space, also involves the material imposition of sovereign political power through such fixed spatial units. Citizens and non-citizens alike thus find themselves frequently caught in the deadlock of territory as it provides no alternative space for making a life and developing a livelihood outside of its constraining perimeters. With sometimes paradoxical results.

courtesy Nick Hannes