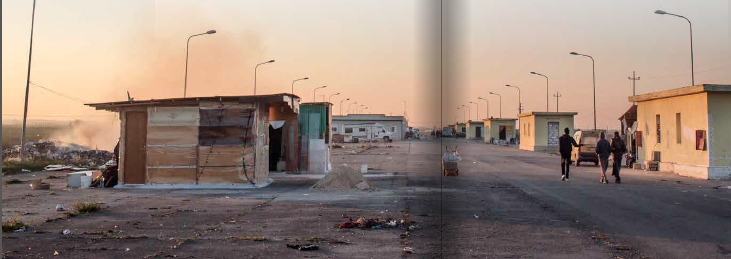

More questions arise around the fire that destroyed the ghetto of Rignano last Thursday, only hours after police had moved in to forcefully evict its residents. As I wrote yesterday, the fire claimed the lives of two Malian citizens, Mamadou Konate (33) and Nouhou Doumbia (36), whose bodies were found carbonised in one of the destroyed barracks. Mamadou and Nouhou were among more or less hundred residents who refused to leave their homes in the aftermath of the eviction. For fear to loose their belongings, and to be turned away from their bosses (the caporali who practically run the labour rackets around here), they decided to stay put, paying with their lives.

During a protest march organised on Thursday, immigrants had already denounced the lack of available accommodation, which, for the 3-400 remaining day labourers, risked to close their opportunity to work for good. Regional authorities mention 320 beds in two facilities: Arena and Casa Sankara. Both are closely supervised by the police now, officially for fear of retaliations from the part of the capi neri -or African caporali. In a statement to the national press, regional governor Michele Emiliano ensured that soon, his administration would prepare “ways in which any worker who comes to Puglia will find accommodation with the help of different organizations, including agricultural enterprises and the state, to ensure that employment in agriculture is not in hands of the capi neri who control this field in criminal fashion (mafiosamente), but it is in the hands of institutions, enterprises and the Puglia Region.”

But while state authorities are joining efforts to blame the deaths of Mamadou and Nouhou on their fellow nationals, questions arise as to the coordination of police forces in the ghetto area. After a delegation of immigrant workers had tried to convince the attorney of Foggia in vain to leave the ghetto open for the next agricultural season, some immigrants decided to return to Rignano. The question now rises how the fire could spread through the night under the full presence of carabinieri, police and fire brigades. The next day, when Mamadou’s and Nouhou’s bodies were discovered, Foggia’s attorney (prefettura) was quick to deny any malicious intent. But on Saturday, superintendent Antonio Piernicola Silvis publicly raised the suspicion that the fire had been ignited deliberately. Commenting a video spread by Corriere della sera, where several immigrants appear to laugh at the event, he commented: “in the area 7-8 well-known subjects were involved, who were stirring up the others to leave. Probably they did not want to kill anyone but … you know, in these situations, fortune takes a hand.” The video effectively shows a few burning barracks, but those who are laughing rather do so with a grim: one person cynically says, in Wolof: “look at the destruction… because of one man, a thousand people will loose everything, where will they all sleep now?”

In the meantime, another video -which was not made publicly available- shot by the national Air Force during the eviction could possibly eliminate some doubts. According to one source, it clearly shows how Thursday’s fire spread simultaneously from several points within the ghetto. The superintendent has now opened an investigation into manslaughter.

Several questions are raised now as to the efficacy of the anti-ghetto operation. First, the rapidity of the intervention has, unwillingly, caused a number of victims. While fire workers worked hard to quench the flames on Thursday, unfortunately help came too late for two Malian citizens,

Several questions are raised now as to the efficacy of the anti-ghetto operation. First, the rapidity of the intervention has, unwillingly, caused a number of victims. While fire workers worked hard to quench the flames on Thursday, unfortunately help came too late for two Malian citizens,