I share a reflection by Adia Benton on the development of the recent COVID-19 emergency, which I think is worth reflecting on:

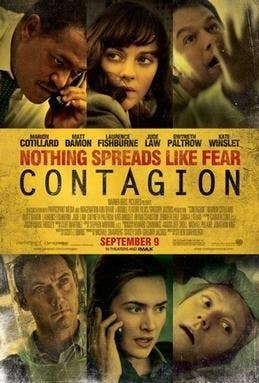

Very rightly I think, Benton argues against the conventional outbreak narrative, where a new, deadly virus emerges in the scandalous intermingling of Asian or African native species and ‘man’, circulates along well-traveled business routes, and is unleashed on the Western world through illicit intimacies. This linear geography – which she picks up from the famous movie Contagion – strongly misses the point about the way the recent COVID-19 disease spreads and affects the world. Viruses move in bodies, she notes, and thus the relative freedom of certain bodies to move across borders as well as the perceived risk associated to this mobility definitely deserves more attention at a time when national security and territorial borders appear to become again a dominant paradigm in international politics.

At a time when governments increasingly wage their wars against the national contagion of a disease, which -as the epidemiologists keep repeating – ‘respects no borders’, it becomes clearer and clearer that its mobility is actually more networked and rhizomatic than state governments are willing to accept. Mind for example the recent Malta, Slovenia and Austria closures with Italy as well as the Trump administration’s continuing flirtation with the same idea. Such territorial containment and its related, racist imagery of the evil outsider may well help ‘put a face’ on an otherwise unidentifiable danger, but it risks to create an illusion of national security at a time when mobilities are regulated increasingly through other, more subtle technologies of diversification and control.

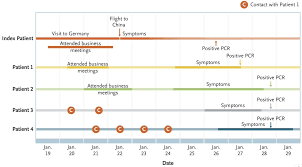

One small irony in this context has been the progressive acknowledgement that the infamous Patient One, a businessman who was hunted down for weeks in the Italian region of Lombardy, actually brought the virus over from neighbouring Germany; on the way, infections of the same cluster (named Germany/BavPat1/2020) have been identified throughout Switzerland, Finland, Mexico and Brazil. Although the evidence on this cluster is far from definite, it appears to confirm Benton’s thesis that indeed certain forms of border promiscuity and certain forms of border containment are accelerating the wider infectious consequences of COVID-19 throughout the world.

Another interesting point Benton raises, concerns the largely neglected political ecology of contagion. At a time when humanity is thought to have acculturated nature completely and the consequences of its extractivist expansion are spreading throughout the planet, the COVID-19 emergency does force us to reflect a bit more deeply about the wider implications of these anthropogenic interventions, not just in terms of global ‘risk management’ but also in terms of nature’s response. Benton uses a prop from the 2011 film Contagion, which ironically may contain some elements for such future reflection: the Nipah virus the film talks about takes off from the intimate contact between a bat, driven away from the tropical forest (literally flying off from a chopped palm tree), a slaughtered pig and a business women who shakes the chef’s hand in a casino restaurant before setting off on her global travel, contaminating the rest of the world. Next to the openly gendered and racialised imagery this film projects, it also poses two crucial questions for us to answer in a preferably not so distant future:

- what level of (calculable) risk is humanity globally willing to accept to sustain its current level of (certainly unequal and diversified) growth and welfare?

- And what kind of interventions are needed to distribute this risk in a geographically sustainable manner?