Just as the European Union is passing on legislation aimed at stopping the financing of armed groups through trade in conflict minerals this week, the consensus is growing that a similar legislation passed under Obama in the US has had a negative effect on livelihoods. A new report by the IRIN press agency published on 6 April demonstrates how campaigning organisations that were a driving force behind the Dodd Frank legislation have barely acknowledged its pitfalls and continue to promote overly simplistic narratives, despite mounting evidence that the act has neither been as effective nor as harm-free as desired. While one of them (Global Witness) in February belatedly acknowledged that the “market’s response [to the law] affected the livelihoods of the thousands of artisanal miners in eastern Congo”, all failed to address the fundamental point: that sealing off produce from so-called ‘conflict-free mines’ has tended to create monopolies (or rather, oligopsonies), which, in turn, favour lower prices for miners and thus affect their livelihoods negatively -not to talk about what happens to those miners who don’t have the privilege to work for ‘conflict-free’ markets. So while most actors agree that the law has had some benefits (like raising awareness that armed groups, in particular the national army, shouldn’t profit from the mining trade; and forcing companies to find out what happens in their supply chains) the IRIN investigation reconfirms that mining communities were never properly consulted, on the contrary: most support for the law now is coming from groups that don’t accurately represent the miners’ interests, in a country devoid of real political representation. More discussion is certainly going to arise around this issue, as the cracks in the conflict minerals campaign (including harsh critiques by former campaigners) are becoming increasingly evident.

Category Archives: conflict minerals

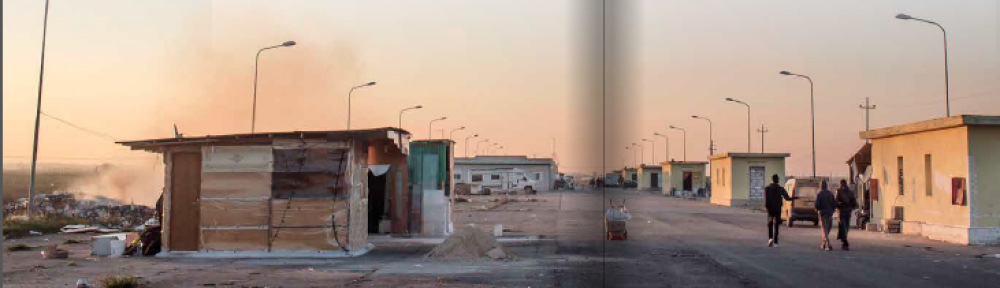

The Terror of Peace

Please allow me to post somewhat lately this reply to my joint piece with Christoph Vogel about the transformative effects of conflict minerals regulation in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). I rediscovered the piece just as the bodies of two UN experts have been found in Kasai, along with their driver and translator. Human Rights Watch expert Anneke Van Woudenberg described this unprecedented attack as “devastating news” and “a blow to the crucial work on … sanctions violations” (on twitter). Although the two reports are unrelated, the New York Times reported on the day of their disappearance the arrest of seven Congolese Army officers who were charged with war crimes, after a video surfaced last month that appeared to show uniformed soldiers opening fire on a group of civilians in a massacre that left at least 13 people dead, including women, and possibly children. Apparently the UN experts were investigating mass graves in the same area… These terrible news show how, rather than expressing a “the privilege of an academic viewpoint“, investigations such as these into the messiness of current ‘post-war’ tensions -including around resource access- continue not only to be necessary, but are often paid dear by those who, like those UN experts, have the courage to denounce abuse.

Trump on conflict minerals

After a long silence I got caught last week by an intriguing report on conflict minerals (a theme I have worked on for some years). Donald Trump -already infamous for his tough stance on immigration -made himself unpopular among several international aid organisations by announcing the partial abolishment of the Dodd Frank reforms (also know as ‘Obama’s Law’). News agencies reported a two-year suspension of regulatory controls designed to prevent US companies from importing so-called ‘conflict minerals’ from Central Africa. The Trump administration motivated the executive order (see leaked memo here) by citing “mounting evidence” that current blood minerals regulations are causing serious harm to some parties in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and, as a result, are contributing to instability in the region that could threaten the national security interests of the US.

Apart from the expected outrage of international campaign groups (Global Witness called the Trump order “a gift to companies wanting to do business with the criminal and the corrupt“), some voices from Eastern DRC appear to partially confirm the US’s fears. A recent IRIN investigation -notably written by a former Global Witness campaigner- claims to find merit in Trump’s observation that conflict minerals legislation is, indeed, leading to a loss of livelihoods in the region -in addition to the already massive repression of artisan miners’ rights. The IRIN report (a first of two, apparently) further confirms existing evidence –amongst others gathered by myself and my PhD student Christoph Vogel– about the detrimental impact of pilot projects seeking to implement ‘transparent commodity chains’ from Eastern DRC.

At this stage, it is difficult to estimate what to make of the current US stance on conflict minerals. Apart from clearly being ‘anti-Obama’ (just like any order Trump has signed so far), the leaked memo does not seem to take a clear direction towards an alternative legislation -which is worrying many observers. Since the ‘no conflict minerals’ rule came into effect, the US has effectively lost much of its minerals suppliers from Central Africa to China and the Far East. Besides its unconditional protection of US companies’ interests abroad -no surprise in the current constellation- the US administration is indeed recording a certain opposition towards international human rights campaigns in Central Africa. In the face of falling prices and trampled miners’ rights, the effect of this development -which literally risks to move from a negative, ‘no blood minerals’ closed door policy, to an even more negative ‘no rules at all’ -is likely going be felt most severely at the lower scales of the commodity chain: on the shoulders of those workers who continue to supply our phones and computers with highly performative minerals, without any form of protection, representation, or rights.