For the next 23 days still, Swiss television is showing a documentary on Palazzo Salaam –the occupied former University building in the southeastern Roman periphery that has recently been threatened with closure by the Renzi government.

For the next 23 days still, Swiss television is showing a documentary on Palazzo Salaam –the occupied former University building in the southeastern Roman periphery that has recently been threatened with closure by the Renzi government.

Author Archives: admin

Europe’s bordering business

While the corpses of migrants who died during Sunday’s boat disaster are still washing ashore together with few survivors, and a special EU council meeting today debates ever more repressive border controls across the Mediterranean, media reports the arrest of a ruthless racket of human traffickers that is apparently tearing a gaping hole in Europe’s border control policies. An enquiry into the business of migration.

Rebuffing the EU proposal on migration

The following post summarizes a concrete rebuffal of the current EU proposal (debated by the EU Council today) to combat ‘illegal’ migration by Italian scholar Fulvio Vasallo Paleologo

The paradox of territory

In Italy, quite a number of occupied buildings I previously indicated – inspired by Heather Merrill – as ‘black spaces’ (the shelters, detention centres, condemned urban buildings, and other locations representing those who, by virtue of their asylum status and association with African territories, are rendered non-citizens, even though they are an integral part of modern Western societies and the economies that sustain them) are currently threatened with eviction.

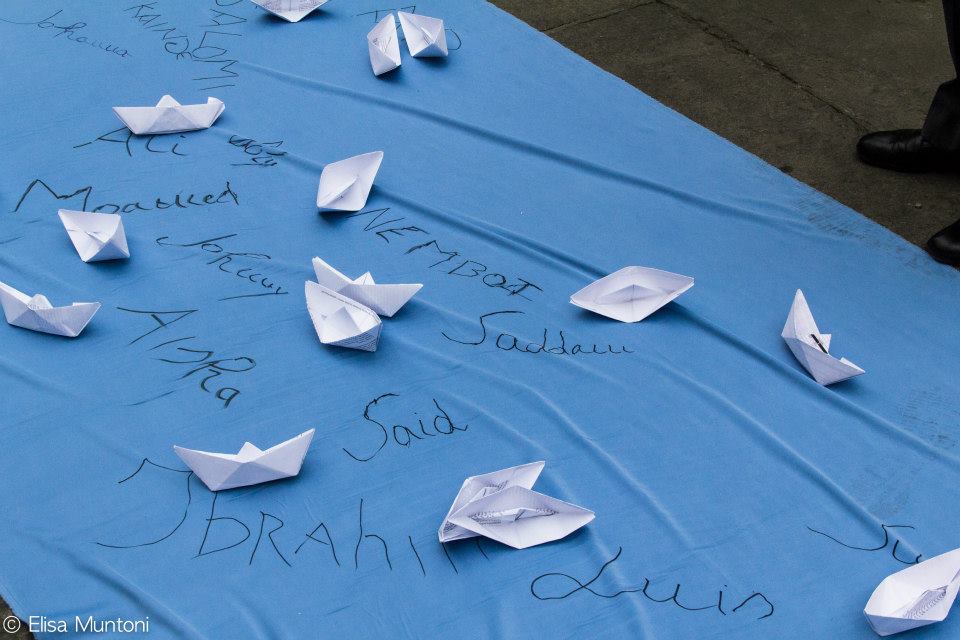

In Turin, the occupants of exMOI, 750 refugees from 26 different African countries (apparently including 15% are women and 30 children) have been ordered to pack and leave. During their March last Saturday, they carried huge banners depicting their Black mediterranean presence.

In Rome, the occupants of Palazzo Salaam (an estimated 1.200 refugees and beneficiaries of humanitarian protection, mostly from the African Horn) loose their residence permit as a result of the new housing legislation proposed by the Matteo Renzi government.

In Bologna, 200 families occupying exTELECOM, a building opposite the new city council, are threatened with eviction.

Given the chronic shortage of places to host refugees and asylum seekers across the country, UNHCR and Medici per i Diritti Umani, a medical charity, estimate, thousands of asylum seekers and beneficiaries of international protection are living in precarious housing conditions. For example in Turin, a local migrant association estimates that around 600 refugees and people benefiting from a humanitarian protection status live across 7 occupied buildings in the city. Considering other such ‘black places’ in Bologna, Rome, and Florence in this calculation, the numbers easily add up. This number does not even include the homeless refugees whom, as one Malian who fled to Germany explained, are sleeping under the bridges of Italy’s metropoles.

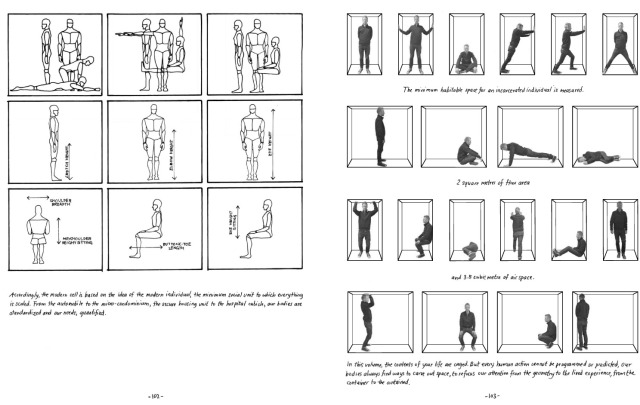

The paradox lies precisely in the new housing legislation (or ‘piano casa’) that was voted in 2014 but is being put into practice only recently. Article 5 of this plan says: “Whoever occupies a property illegally without title cannot apply for a residence nor for a connection to public services in relation to this property, and [by consequence] all acts in violation of this prohibition shall be declared null in front of the law.” The converted law (voted in March 2014) is even more severe: “Those who illegally occupy residential public housing cannot participate in the procedures fro obtaining housing for five years following the ascertained date of the illegal occupation.”

Besides the curious liaison between residential property and public space in this legislative measure (residential public housing), the concrete application of it means that whomever occupies a building of black of better alternatives, can be denied official residency. This poses a source of anxiety particularly for the refugees and asylum seekers whom since the Nord Africa Emergency of 2012-2013 have been thrown out in the streets for a lack of assistance by the (theoretically) protecting state.

The comment by Antonio Mugolo, president of Avvocati di Strada, an association that takes up the defence of homeless people in Italy, is telling in this respect: “Without residence,” reminds Mumolo, “you cannot vote, you cannot cure yourself, you cannot receive a pension nor benefit from local welfare, you cannot obtain formal employment, you are not entitled to legal assistance … [In short] taking away the residence permit from people who occupy a building literally means placing those people outside of society, making them invisible, erasing in one single shot the possibility to confront their difficulties… It is remarkable that a plan, which should help families to confront the crisis, precisely bears these consequences,” he concludes.

Somehow this situation reminded me of the inherent violence expressed in the term state territory. So whereas, on the one hand, as Stuart Elden would say, territory is a political technology to measure land and control terrain, territory is also the effect, the product of spatially fixing relational networks into this bounded space. Close to Michael Watts‘ and David Delaney‘s reading, the legislative measures I briefly illustrated above indeed illustrate the consciously violent (or ‘terrorising’?) work of territory, which, besides its calculative techniques, of marking, bordering and categorizing political space, also involves the material imposition of sovereign political power through such fixed spatial units. Citizens and non-citizens alike thus find themselves frequently caught in the deadlock of territory as it provides no alternative space for making a life and developing a livelihood outside of its constraining perimeters. With sometimes paradoxical results.

courtesy Nick Hannes

Detained Voices

After the suspended lives of Berlin and Milan (see previous post), this time a call arises from the more secluded spaces of Europe’s asylum system, as hundreds of people are on hunger strike in over half of the UK’s immigration detention centres – the biggest uprising against Britain’s racist detention system for a decade. Two blogs record their detained voices on this worldpress site and on this Facebook page. They are calling for solidarity protest and international support.

.

Suspended

Watching Theo Angelopoulos’ movie To metewro vhma tou pelargou (The Suspended Flight of the Stork) the other night, Mustafa Dikeç’s comment about the ‘where of asylum’ came back to mind (see previous post: Where is the Law?).

This rather less recent movie (it dates form 1991) tells the story of a famous Greek politician who disappears to a village on the border with Albania (it is the first of a trilogy on borders by Angelopoulos). The village acquired the nickname ‘Waiting Room’ since the refugees the Greek government placed there, are waiting for their visas for elsewhere. But after years that ‘elsewhere’ acquires a rather strange meaning, the journalist, who inquires about the politician’s disappearance, notes in the movie.

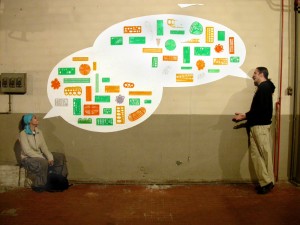

Greece and the Mediterranean have changed much since these early days after the end of the Cold War. Many ‘Waiting Rooms’ have emerged now within Europe’s national borderlines: in Athens’ Exarcheia neighbourhood, in Tel Aviv’s Lewinski Park, in Milan’s Porta Venezia, on Berlin’s Oranienplatz, migrants flock together to confront experiences and plan their onward journeys -often accompanied by activist networks. Next to the constant tensions their experiences and hopes generate in Europe’s internal border zones, these ‘waiting rooms’ are also often liminal places, characterized by a creative energy and re-constellation of identities that have the potential to transform social and political relationships.

By way of example, I mention two documentaries, Asmarina by filmmakers Alan Maglio and Medhin Paolos about Porta Venezia, and Lampedusa in Berlin, by Mauro Mondello, which narrate these emergent realities of Europe’s liminal ‘waiting rooms’.

Where is the Law?

Society and Space just published a marvelous virtual theme issue on international migration, with contributions from Rutvica Andrijasevic and William Walters, Deirdre Conlon and my former colleague Susan Thieme, amongst others.

The collection adds further depth to the ongoing discussion in critical legal geography on the complex and expanding spaces of the law, expressed for example in a recent collection edited by Irus Braverman and others. These authors draw in turn on a long-standing scholarship of legal anthropologists like the Von Benda Beckmanns, Boaventura Santos, legal geographers like Nicholas Blomley and David Delaney, and legal scholars like Zoe Pearson and Oren Yiftachel.

In the guest editorial of Society and Space, called ‘the where of asylum’, Mustafa Dikeç asks the pugnant question:

“Does law produce spaces where it no longer applies? Does it, in other words, set up spaces of lawlessness?”

Parallel to Irus Braverman and colleagues, Dikeç addresses this question not merely from a practical legal perspective (how law is shaped) but out of a profound curiosity into power’s spatial constitution, as John Allen would put it.

What animates this growing body of work, Dikeç writes, is the idea that law may be involved in producing spaces of lawlessness. In other words: violence that is commonly depicted as ‘lawless’ may actually be committed through the law –or rather: through the continuous reproduction of its exception. It is this latter strand that seems to be the main concern of contemporary legal-spatial research.

Dikeç’s question came to mind lately when watching a series of recent Italian documentaries on the expanding migrant ‘ghettos’ in Puglia, Campania and Basilicata (the issue is generating worldwide attention nowadays, some day I need to produce a list of recent contributions). Set up as labour camps for the numerous seasonal land labourers (or braccianti) who invigorate South Italy’s plantation economy, these ‘ghetto’s’ reflect the extremely violent and exploitative forms of encampment capitalist labour regimes engender across international borders today (not to speak about the strong semantic resonance of the term). But they also express how the law (particularly asylum law) consciously creates it own exception, which is henceforth placed outside of its protective realm.

In other words, the conscious abandonment of protection as a fundamental value of state sovereignty within the EU’s national state frameworks is not just made possible through the systematic prevention of access to its territory, or the official detention of migrants across Europe’s many camp sites. But it is also justified through the reproduction of these liminal environments, which simultaneously constitute the law’s outer-space – or frontier zone – and the inner space of cross-border capitalist undertakings. Reflecting on Europe’s schizophrenic hospitality, Andreas Oberprantacher writes:

It is crucial to realise, however, that it is not just states that are implicated in the creation and management of a heterogeneous population of illegal aliens, but also actors that are usually acting in concert with liberal democratic states, so that two major elements of the rule-of-law, that is jurisdiction and accountability, are effectively diffused in a rather viscous and all-too-often treacherous frontier regime.

Somebody who has been working on the transformation of the state’s legal space theoretically more recently is David Delaney. In his recent book, Nomospheric Investigations, he tries to overcome the discrepancy between the legal and the spatial as two autonomous realms. The nomosphere is the cultural-material environment that emerges out of the performative engagements through which the social signification of the ‘legal’ and the legal signification of the ‘social’ materialize and mutually constitute one another. At the same time Delaney makes it plain that nomic settings, like the home, the archive, or the workplace, do not exist in isolation from one another. But they are the contingent products of pervasive cultural processes associated with the nomosphere (he uses the term nomoscapes). His work feels reminiscent of feminist scholarship about the location of knowledge (I think of Donna Harraway and Bell Hooks for example) as well as some of the more recent critical scholarship on borders (of which the Society and Space theme issue is just one recent outcome) I look forward to engage more in-depth with.

conflict tomatoes

An interesting article in The Guardian yesterday mentioned the term ‘conflict tomatoes’ –a remarkable term given its legacy in denouncing corporate complicity with financing warfare (images of the movie Blood Diamond immediately spring to mind, but also of coltan, and Congo). Echoing my earlier post on heterogeneous market associations, the Guardian writes how British consumers in particular are being consciously misled. Sweet mixed baby tomatoes sold by supermarket giants Tesco and Morrisons, and which have been labeled as produce of Morocco, in fact are cultivated by giant agribusinesses in the contested area of the Western Sahara. Some of these businesses are property of the wealthy King Mohammed VI, others of powerful Moroccan conglomerates and French multinational firms.

The term conflict tomatoes first came up in a joint WRSW-Emmaus report produced last month, which denounces the upcoming trade agreement between the EU and Morocco that will open the Union for large imports of agricultural products from Morocco. Morocco, however, is an occupation power, it writes. And the deal can be used by plantation companies in occupied Western Sahara to export fruits and vegetables to EU supermarkets free of tariffs and under the veneer of a an internationally ratified agreement.

I am curious to what extent research will follow up on the effects the massive displacement this extensive agricultural production rise will obviously generate both locally and transnationally (in the same logic as West African farmers now are joining the ranks of Europe’s precarious labour force in the agricultural sector as a result of aggressive capitalist expansion they face at home).

At the same time, the terminology of the ‘conflict tomato’ also opens up a whole new spectrum towards this kind of aggressive agricultural frontier developing in and South of the Sahara. Contrarily to the earlier campaigns against conflict diamonds that concentrated predominantly on the role of non-state actors and shady businessmen, for example, advocacy organizations like WSCUK are explicitly criticizing the role of states and multinational corporations. Maybe this ‘unusual take’, as the Guardian calls it, will also help enrich the conceptual scope of the conflict minerals debate towards a wider critical understanding on such changing global constellations of economic appropriation and development.

Border Art (take two)

Since my last posts mentioning border art and the Black Mediterranean, I’ve been receiving some additional suggestions. In the following post I discuss some of them.

Follow the Tomato!

Following my earlier post on the racial geography of the Black Mediterranean, colleagues keep pointing me at North-South connections in agri-food commodity chains, particularly with regard to tomatoes. My colleague Christian Berndt, for example, has written this wonderful comparison between the EU/North Africa and US/Mexico borderlands together with Marc Boeckler (click here for pdf and here for a link to the edited book chapter). They adopt a consciously marginal perspective – a view from the border – to document the heterogeneous associations that literally connect the agricultural fields to the supermarket shelves.

Following my earlier post on the racial geography of the Black Mediterranean, colleagues keep pointing me at North-South connections in agri-food commodity chains, particularly with regard to tomatoes. My colleague Christian Berndt, for example, has written this wonderful comparison between the EU/North Africa and US/Mexico borderlands together with Marc Boeckler (click here for pdf and here for a link to the edited book chapter). They adopt a consciously marginal perspective – a view from the border – to document the heterogeneous associations that literally connect the agricultural fields to the supermarket shelves.

“In tracing the network tomato we posed one central question: How is the tomato held stable as a tomato while it is not only displaced through space but also subject to multiple ways of b/ordering that try to control the double play of framing and overflowing?”

The authors interestingly conclude with a quote form Ulrich Beck: “It is not the dissolution of borders, but rather border negotiation and border work which is at the heart of current globalisation processes.”

Their approach reminded me of the original approach taken for example by Ian Cook et al. (Follow the Papaya). As Cook writes while following his papaya from the field to the plane, to the London supermarket, and to the fruit bowl:

Although the narrative appears linear, it is not, as cross-cutting connections are drawn among and outside its constitutive stages: to colonialism, to the World Trade Organization (WTO), to Western middle-class consumption aesthetics, to the diseases and pests of exotic fruits, to the character of international air cargo transportation, and to developing-world labour control and surveillance. This is an unbounded, dense network of associations. And precisely because it isn’t a simple chain, the commodity itself is no ‘trivial thing’; it is composite, defetishized, decrypted, reflecting all manner of trace effects.

Years ago I remember seeing this Brazilian documentary that followed a tomato from the field -where it grows, is watered, taken care off, and then, as it is further transported, sold and carried home, it ends up in the garbage of one wealthy family in Rio de Janeiro (unfortunately I cannot find the documentary any more, if anyone can give me a hint that would be highly appreciated).

A friend journalist then mentioned this feature on the Dark Side of the Italian Tomato by Mathilde Auvillain and Stefano Liberti.

“Makola market, the main market in Accra – one of the largest in Western Africa – is the commercial heart of the capital (…) Everywhere, wooden stalls seem to be laden down by red tins of tomatoes, skilfully balanced by the sellers in mysterious geometric formations. (…) “Salsa”, “Fiorini”, the brands are Italian pastes (…) even the Chinese product “Gino” displays the Italian tricolour on the tin to attract customers.”

“(…) the government should have limited the quantity of tomato paste coming in from abroad. “If the market had been regulated, the farmers would’ve gotten better prices and would’ve had a market for their produce. But the government did the exact opposite. It swung open the doors of the country to imports of European tomato paste. Now there’s such a wide choice and such an amount of produce that it’s practically impossible to sell locally-grown tomatoes”.

The webdoc concentrates amongst others on the swamping of African markets by European and Chinese tomato paste. What I didn’t know is that many of the African day labourers who end up picking tomatoes in Southern Europe come from tomato growing regions themselves; as a result of commercial dumping, these producers often have no other choice than to re-enter the commodity chain as unfree labourers. Bernard Hazard already mentioned Béguédo in Burkina Faso. The documentary by Mathilde Auvillain and Stefano Liberti furthermore mentions Upper east Region in Ghana. This raises the further question how African seasonal workers are recruited, how their labour force figures in a wider restructuration of agri-commodity chains dominated by big retail businesses, and how informal employment schemes intermingle with formal border regulations.

Finally last week, I became acquainted with an alternative way of organizing local tomato productions during a fair organised by SOS Rosarno. With their help, a group of African producers from Venosa, Basilicata, proposed their product, bottled tomato sauce, which says ‘free from labour exploitation’. Labourers are regularly employed without the intervention of criminal intermediaries, or caporali.