Monthly Archives: April 2016

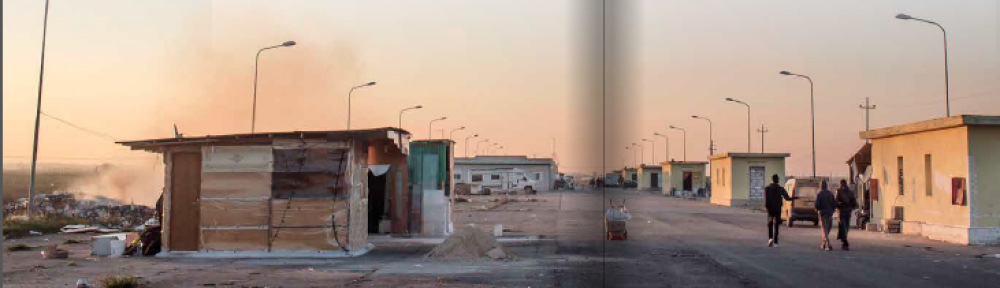

Pro/fuga

An interesting report on Pro/fuga and the way it tries to confront the exploitative conditions of migrant workers in the Foggia area of Puglia, Italy, just came out on Meltingpot. Definitely worth the read. More information on the current situation is being regularly collected by OMB.

Sacrifice

Further to my previous post about Brussels some days ago, two apparently unrelated analyses appear to confirm my observations about the reasons behind IS expansion. According to terrorism expert Hassan Hassan, the strategy of hitting targets in Europe, far removed from their operational bases in the Middle East and Northern Africa, is increasingly unrelated to the loss of terrain they are experiencing in the latter. On the contrary, the attacks in Paris and Brussels show how IS is trying to take control over former Al Qaeda networks by aligning and associating themselves with the latter’s militants.

Further to my previous post about Brussels some days ago, two apparently unrelated analyses appear to confirm my observations about the reasons behind IS expansion. According to terrorism expert Hassan Hassan, the strategy of hitting targets in Europe, far removed from their operational bases in the Middle East and Northern Africa, is increasingly unrelated to the loss of terrain they are experiencing in the latter. On the contrary, the attacks in Paris and Brussels show how IS is trying to take control over former Al Qaeda networks by aligning and associating themselves with the latter’s militants.

In an unrelated analysis, Scott Atran -an anthropologist working in France and the UK- warns not to underestimate the ideological traction of the IS Caliphate. In the poor neighbourhoods of Casablanca and Tetuan, as in the Parisian banlieus, he and his colleagues encountered a widespread acceptance, if not a sharing, of IS values as well as the brutal violence committed in its name. Despite some of the factual mistakes in Atran’s text (which are discussed in part on the Aeon forum) the key message is valid and lays in what Edmund Burke, in a different context, calls the attraction for the sublime -or the fascination to fight for a glorious and unifying cause.

Far from being miserable paupers, or a rejected Lumpenproletariat (as Diego Gambetta showed for other historical examples), IS suicide bombers not only share this fascination, but they are also ready to make the ultimate sacrifice in favour of this greater good as well as for their group of companions with whom they share intimate relationships (Atran talks about a fusion of identity in this regard). In this sense it does not come as a big surprise that the large majority of IS recruits are mobilised through their proper families, the French centre against religious radicalisation (or CPDSI) reveals. Rather than more police and camouflage on the streets, therefore, what might be needed instead are closer contacts with such families at risk as well as community leaders. In their unwillingness to also address the socio-psychological causes of this terrorist (or, as Atran provocatively says, “revolutionary”) struggle, European leaders continue to play into the cards of the IS military leadership, which is becoming increasingly apt in exploiting this diminishing grey zone between the sovereign life of post-modern (neo)liberal democracies, and the killing of this life in the name of revolutionary sacrifice…

Doreen Massey

Sadly receiving the news about the passing of Doreen Massey, I would like to flag two obituaries that describe well her life-long dedication to an understanding of space that is “complex, porous and relational,” as Noel Castree put it. Massey is, concretely, the reason why I am in(to) geography now. I still remember my colleague flagging up her brilliant piece Politics and Space/Time when I was about to finish my PhD. Together with Michael Watts’ ‘Sinister Life‘ it greatly influenced my thinking for the next decade. So I am extremely grateful to Massey -and to my colleague of course- for having brought me onto this path. Words can’t describe her career better than these two separate obituaries by Noel Castee (for PiHG) and David Featherstone (for the Guardian).

After Brussels

I’ve been willing to write something about Brussels for a while now, but somehow I missed the words. Other than the tragic loss of 32 lives, the wounding of many others, as well as the fact that the attack took place in Belgium, where I was born, in an airport where I’ve passed dozens of times, a metro I regularly took, perhaps the most sobering aspect of the 22 March attacks has been the widespread resignation with which they have been received. Contrarily to Paris and New York, there were no patriotic speeches on the rubble of crumbled buildings; and few were the propositions to ‘smoke out the terrorists’ from their ‘caves’ and hideouts.

One reason might be the awareness that the neuralgic centre of the attacks lay a few miles from where they took place this time. In that respect, it’s been ironic how Brussels, and Belgium by extension, has quickly acquired the epithet of the ‘failed state’ in quite similar ways Afghanistan or Somalia continue to be described by some conservative think-tanks like the Fund for Peace. Driven by almost revanchist undertones (for example in these reflections by Tim King and former war reporter Teun Voeten for Politico), Belgium’s dysfunctional federalism is taken as a mirror for the ‘lawlessness’ and rising radicalism in the Brussels neighbourhood known as the terrorists’ headquarters. Such analysis not only glosses over the systematic institutional hypocrisy with regard to the city’s, admittedly, major problems (which are confronted with the usual mix of militarisation and social neglect) but it also mistakes such wider social unrest for the jihadi’s personal motivations. Besides the fact that Belgium still produces more foreign fighters than any other European country, one must not forget that none of the attackers (neither of Paris nor of Brussels) were interested in radical Islam until very late before they decided to dedicate themselves to the armed struggle. Observers, like Olivier Roy and Fabio Merone, who know the wider recruitment basis of ISIS in Europe a bit, all agree that the religious extremism of these young people is nothing more than anger dressed as Islam. Otherwise how do you explain that Abdelsalam Salah was “drinking beer and smoking joints” a few weeks from the attacks of the Bataclan, as some of his friends recalled in front of the cameras…

In that respect I much more preferred a report by l’Espresso (unfortunately not translated into English) which places the reasons for this rage in the socio-cultural divide between first and second generation immigrants, and the fact that immigrant youth risk to see their host country and their parents as traitors of a failed life project (or, as one foreign fighter explained to his mother shortly before he left: “If I had blond hair and be called Jacques I would most likely be sitting at my comfortable job at the commune, but with my Arab name I can’t even find work as a street-sweeper”). Even if this sounds absurd for the majority of muslim youth in Belgium, ISIS has become very apt at exploiting the projects of revenge that germinate in a life enmeshed with boredom, frustration and petty criminality for a minority of them in very similar ways as the Camorra has taken grip over its strongholds of Scampia or Castelvolturno in the Italian de-industrialized South. With the only difference that ISIS does not (just) promise money and power but also paradise. Feeling rejected by their homes, organised violence provides for these youngsters a new family in many respects -awkward as it is.

But BXL22M also forces us to consider more seriously the changing geography of global warfare these days. Besides the risk of urban conflict strategic think thanks warn for (of which Brussels has been another prominent example the last few days), global jihad cannot be limited to a war ‘in the borderlands’, but it also comprises a wider structural basis in the many de-industrialized cities of the North that continue to germinate frustration and revenge. How to connect these dots will be an important task for the future, as will be the challenge to avenge right-wing extremism that is rising at equal pace.