Given my experience with armed conflict, people have been asking my opinion about the terror attacks and anti-terror operations in Paris and Belgium. Despite the rhetorical proliferation around this issue, I add two small reflections. I could summarise them in these two, very short statements:

1. ‘we are them’ –or the collapsing scale of global military engagement in the (post?)-War on Terror age.

2. ‘they are (like) us’ –or the paradox of an emerging global society

I know what war is like: I have seen it, I have touched it, I have smelled it. Therefore, I know what small groups of armed young men can do to society; I’ve seen how it happens, and continues to happen, in the rural backwaters of North Kivu, in Nigeria, in Sudan, Somalia –as well as in the streets of Sarajevo, Kabul and Baghdad. I also experienced personally how political antagonism can quickly transform into outright polarization, an open rift that makes it difficult, if not impossible, to express moderate opinions and live one’s everyday life across social and ideological boundaries. And I’ve seen what misguided military interventions can cause in terms of popular frustration, political setbacks, and even escalating violence.

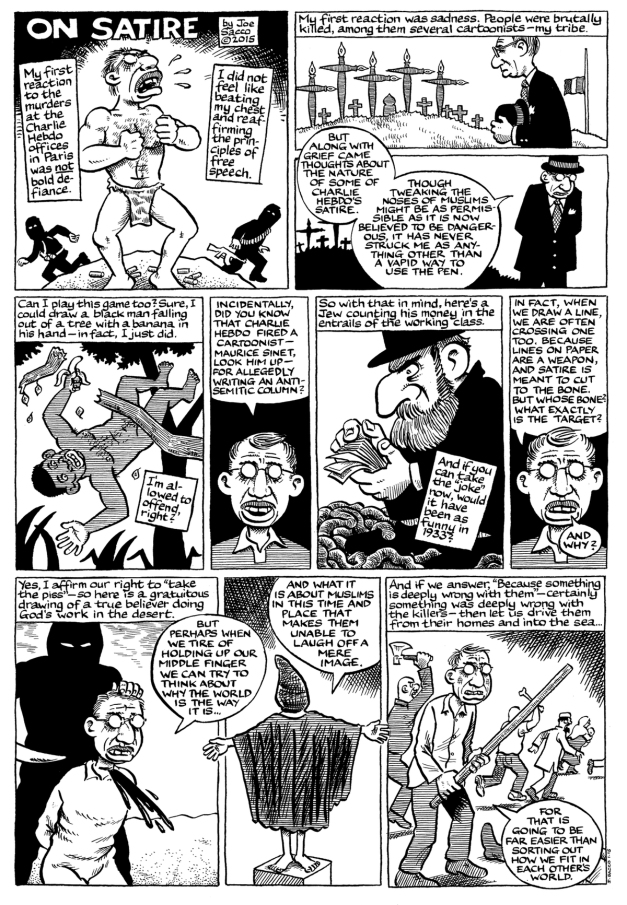

That is why my first feeling with the liberal consensus around Charlie-Hebdo’s blasphemic iconography has been one of growing consternation. In the days after the attack, public manifestations quickly –and worryingly I think– took the form of a public crusade, of ‘je suis Charlie’ banners and sharpened pencils, in defense of assassinated white intellectuals. This is not to minimize my compassion, neither with the people killed (including, not to forget, a Charlie Hebdo collaborator and a policeman of North African descent); nor with those who were targeted afterwards as a result of anti-Muslim retaliations. But if you compare this ongoing Charlie mantra with average media reactions in, say, West Africa or South Asia, you quickly get an idea of the considerably Eurocentric character of these protests, which –I am not exactly sure yet how to phrase it– underwrite a mixture of national European belonging and liberal democratic values of limitless ‘free speech’. If anything, the dominant reaction in these predominantly Muslim societies was of prudence, if not outright alienation from Charlie’s provocative editorial style. That’s why I appreciate Joe Sacco‘s cartoon, which was reproduced in a few social media, so much.

I personally could think of a few other cartoons. For example of the Kouachi brothers kicking the chopped off heads of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoonists; an onlooking judge says: ‘of course we could not arrest them for playing football could we?’ (the episode refers to the picturesque Buttes-Chaumont park, where jihadists continued to meet and plan attacks despite the massive intelligence on them in Paris; a French judge literally said this). Another cartoon I Imagined depicts Amedy Coulibaly swapping his precarious job at Coca Cola for a permanent contract with ISIS, saying ‘Pourquoi pas?’ I invited more gifted readers to use their pens creatively…

I personally could think of a few other cartoons. For example of the Kouachi brothers kicking the chopped off heads of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoonists; an onlooking judge says: ‘of course we could not arrest them for playing football could we?’ (the episode refers to the picturesque Buttes-Chaumont park, where jihadists continued to meet and plan attacks despite the massive intelligence on them in Paris; a French judge literally said this). Another cartoon I Imagined depicts Amedy Coulibaly swapping his precarious job at Coca Cola for a permanent contract with ISIS, saying ‘Pourquoi pas?’ I invited more gifted readers to use their pens creatively…

In the midst of all this compassion for Charlie’s deaths, it becomes easy to overlook that with the opening of the ‘free space’ inspired by the mourning, other spaces of dialogue and analysis successively closed down.

It has become very difficult, for example, to publicly empathize with the social conditions of the attackers, at least one of whom grew up in a desperate Parisian banlieu, with littered streets, decrepit apartment blocks and a dismembered social welfare state. This, again, raises the urge for an innovative geography of urban migrant marginality, I’d say, to the likes of Mustafa Dikeç and Loic Wacquant for example. After a life dominated by petty criminality and precarious jobs, which, ironically, was raised as a source of frustration during personal conversation with President Sarkozy at some point, Amedy Coulibaly decided to exchange his temporary contract with the Coca Cola plant he had been working at the time for a guaranteed place in paradise. “Je ne suis pas Charlie”? “Je me sens Coulibaly”? In the dominant media climate in Europe, such statements easily get high-jacked in a competing bet for anti-/jihadi & anti-/liberal righteousness.

The sheer visual contrast, which I also find difficult to bear, between heavily guarded Jewish schools and administrative buildings in Europe’s cities, and moderate imams who, in rather defenseless ways, try to establish bridges with other religious leaders and with the general public, makes for a sort of irony that is difficult to capture in this simplistic ‘free speech’ logic. The risk is exactly this: that people start building walls, possible even arming themselves (as this Brussels based rabbi was venturing to propose) in an environment where small weaponry is as easily available as the money to get them (one of the things I learned during my work with the Flemish Peace Institute is that Belgium has been a platform for illegal arms sales since the wars in ex-Yugoslavia).

The risk is that people start building walls around themselves.

Finally –but this has slightly changed after the Belgian counter-terrorism operation– there has been a considerable lack of public scrutiny about the way European governments are (not) tackling (or unable to tackle) the immense problem of militant mobilization –cells of Syria and Iraq fighters, their return, their reintegration, but also a growing mobilization of extreme right militantism– which typically runs in concurrence with marginality and exclusion in the midst of the continent’s rapidly transforming cities. Belgium has the highest per capita ratio of jihadi’s fighting in Iraq and Syria, as this study of the Centre for the Study of Radicalisation published last October shows

So that makes for a first reflection:

As one man on the radio put it: ‘we’ are the others (in the pictures some imagery from the Grande Borne where Coulibaly grew up, which is exactly the kind of estate Wacquant has prompted for his theory on Europe’s rising anti-ghettos). In the constant propaganda of the War on Terror one has become increasingly accustomed on both sides to situate the sources of good and evil in geographically distant places: the idea that ‘our’ wars –clean, civilizing, based on a consistent set of right values and aims- are the opposite of ‘their’ wars –brutal and brutalizing, based on refutable ideas. That illusion has now definitely been shattered.

The pressing problem of IS fighters who have –and will likely continue to– hit Europe in the heart of its moral and institutional infrastructure makes it simply impossible now to situate that ‘evil’ in comfortably distant places.

In fact the blatant irony is that the active distancing of the War on Terror to far-off places like Iraq and Afghanistan has brought the problem of international terrorism back with a vengeance to the center of Europe’s and America’s metropolitan societies.

On the other end, some rightly speculate that IS tries through these attacks to raise its legitimacy by extrapolating, indeed by projecting, its faltering internal coexistence towards an illusionary and distant enemy.

In the same way as European societies have been unable to find their way through multicultural coexistence, leading Islamist movements have been known to struggle hard to deal with the growing distrust and competition between fighters of different origins (the Chechens, Iraqis, Lebanese and their European ‘brothers’ who obviously occupy quite different ranks in the IS hierarchy –this in fact constitutes one of the major sources of disillusion for returning IS fighters, as these letters form French jihadi fighters suggest.

In that respect, Islamism and nationalism clearly constitute each other’s mirror images now as today’s dominant ideologies of popular mobilization. But they do not by any means represent the strategies of military struggle, which are clearly driven by other, more down-to-earth geopolitical interests, as some of the more informed analysis on the global war on Terror suggests ( I recently enjoyed watching Dirty Wars, by Jeremy Scahill).

My second observation is that, paradoxically, this titanic clash of icons between ‘Islam’ and ‘the West’, brings the expression of something like a global ‘society’ potentially closer to people’s everyday sense of place. In the, no doubt, considerably unequal conditions we face in our daily lives, the necessity to take a stance for or against certain ideologies, to make certain choices, and to express one’s values concretely becomes ever more pressing, though not in the ways that exclusive nation-state or religious allegiance are trying to portray.

The War on Terror has collapsed the geographic scale of global warfare in quite radical ways.

Already in the early 2000s, some observers made it apparent that the world was moving towards an expanded ‘network war’, a battle space composed of consciously established connections between the innovative financial, legal and military nodes of the global War on Terror. Emerging training modules (like those for US troopers in the Mexico-US borderlands), as well as a grey landscape of not always entirely legal but certainly expanding modes of military operation in Iraq and Afghanistan is definitely bearing its fruits now in terms of global military escalation -as Derek Gregory writes. In a very straightforward manner actually, American troopers who one day combat ‘illegal’ migration on the US-Mexico border and the other have to transpose their skills to combat the Taliban in Afghanistan, have acquired their perfect mirror image today, of IS militants who learn how to shoot-to-kill in Syria and apply their knowledge on French and Belgian targets. In a way, is this not what the dominant geopolitical reading of the War on Terror has asked for?

Already in the early 2000s, some observers made it apparent that the world was moving towards an expanded ‘network war’, a battle space composed of consciously established connections between the innovative financial, legal and military nodes of the global War on Terror. Emerging training modules (like those for US troopers in the Mexico-US borderlands), as well as a grey landscape of not always entirely legal but certainly expanding modes of military operation in Iraq and Afghanistan is definitely bearing its fruits now in terms of global military escalation -as Derek Gregory writes. In a very straightforward manner actually, American troopers who one day combat ‘illegal’ migration on the US-Mexico border and the other have to transpose their skills to combat the Taliban in Afghanistan, have acquired their perfect mirror image today, of IS militants who learn how to shoot-to-kill in Syria and apply their knowledge on French and Belgian targets. In a way, is this not what the dominant geopolitical reading of the War on Terror has asked for?

These observations of proximity, in my view should make citizens, both in the North and in the South (two other categories that will likely evaporate with time I guess), more aware of what actually binds their faith of exclusion from public scrutiny on global military engagement, for which neither nation-states nor blind religious propaganda has a satisfactory answer. I think we need to start differentiating, between religion and fundamentalism, certainly (why has it become so more bon ton among self-indulgent intellectual circles in Europe to accuse the symbols of religious faith than the -equally disturbing– values of market fundamentalism, for example? Because we don’t see them so clearly?); between irony and disrespect, also (to be honest, is it really necessary to write a novel about the fictitious prospect of radical Muslim rule in France, like Houlebecq does?); between war and terror (are bombs on a bus, onslaughts against the media and military attacks on a state infrastructure all ‘terrorism’? for earlier debates see here for example); between what happens ‘here’ and ‘there’. To conclude, I would like to offer the insight of Teju Cole just days after the attacks agains Charlie Hebdo in Paris:

“France is in sorrow today, and will be for many weeks to come. We mourn with France. We ought to. But it is also true that violence from “our” side continues unabated. By this time next month, in all likelihood, many more “young men of military age” and many others, neither young nor male, will have been killed by U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan and elsewhere. If past strikes are anything to go by, many of these people will be innocent of wrongdoing. Their deaths will be considered as natural and incontestable as deaths like Menocchio’s, under the Inquisition. Those of us who are writers will not consider our pencils broken by such killings. But that incontestability, that unmournability, just as much as the massacre in Paris, is the clear and present danger to our collective liberté.”

Thanks very much to my colleagues and friends for sharing ideas on this issue.