Today and yesterday renewed anti-migrant violence erupted in the city of Rome.

In the neighbourhood of Tor Sapienza, a furious crowd gathered in front of a reception centre hosting unaccompanied minor refugees, voicing their anger against “uncivil immigrants” and calling for popular justice. The inhabitants – around 50 people who set on fire to garbage cans and damaged a police car – said they were sick of serving as a social dumpsite (disscarica sociale) and threatened to take law into their own hands.

In the neighbourhood of Tor Sapienza, a furious crowd gathered in front of a reception centre hosting unaccompanied minor refugees, voicing their anger against “uncivil immigrants” and calling for popular justice. The inhabitants – around 50 people who set on fire to garbage cans and damaged a police car – said they were sick of serving as a social dumpsite (disscarica sociale) and threatened to take law into their own hands.

It is not the first time violence erupts against migrants in Italy and Europe. Three years ago Human Rights Watch voiced its concern into what it called the everyday intolerance against foreign residents – two prominent examples being the multiple attacks, in 2008, against Bengalese shop owners in Rome’s Pigneto neighbourhood and anti-migrant pogroms in Rosarno in 2010. Such episodes moreover confirm a pattern of rising anti-immigrant violence across the European continent. Germany for example has known dozens of attacks against refugee centres since the xenophobic riots in Rostock, in 1992. In the eastern city of Bautzen, asylum seekers recently were ‘protected’ with a high razor wire against angry backlashes from neighbouring citizens.

These xenophobic episodes take place in a climate of spiralling physical abuse against immigrants by civilians as well as state authorities – Italy and Germany once again being imminent cases.

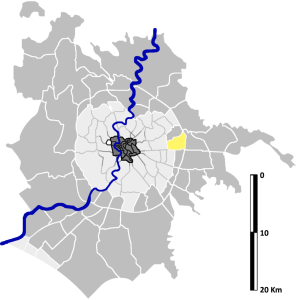

Contrarily to previous episodes of popular outrage, these current outbreaks appear to follow a clear path of territorial stigmatization. It is no surprise, for example, that Tor Sapienza forms one of the Italian capital’s most destitute neighbourhoods. Open prostitution, gang ringing and drug dealing thrive in the desolate fields situated between the A24 motorway and the Tor Sapienza metro station. The strategy of Rome’s city council has been to conflate marginalized groups in this area: north of the motorway, a Rom settlement regularly gets disbanded to arise from its ashes again a few months later – residents complain that their poisonous fumes infest the social housing estates and squats occupied by homeless refugees and asylum seekers close to Via Prenestina (where an autonomous housing project shows that a different way of living together is possible). In Turin and Milan, city authorities employ a similar strategy of housing asylum seekers far away from the city centre, in neighbourhoods that already suffer from an appalling deficiency of transport infrastructure and social services.

Contrarily to previous episodes of popular outrage, these current outbreaks appear to follow a clear path of territorial stigmatization. It is no surprise, for example, that Tor Sapienza forms one of the Italian capital’s most destitute neighbourhoods. Open prostitution, gang ringing and drug dealing thrive in the desolate fields situated between the A24 motorway and the Tor Sapienza metro station. The strategy of Rome’s city council has been to conflate marginalized groups in this area: north of the motorway, a Rom settlement regularly gets disbanded to arise from its ashes again a few months later – residents complain that their poisonous fumes infest the social housing estates and squats occupied by homeless refugees and asylum seekers close to Via Prenestina (where an autonomous housing project shows that a different way of living together is possible). In Turin and Milan, city authorities employ a similar strategy of housing asylum seekers far away from the city centre, in neighbourhoods that already suffer from an appalling deficiency of transport infrastructure and social services.

Confronted with this new form of territorial stigma, as Loic Wacquant would call it (see this free pdf from Environment and Planning), residents of these areas usually respond with a mixture of defiance and resignation. Interesting in Wacquant’s account is that he places this emerging urban policy model into a system of growing spatial taint, where territorial identities – rather than class or race – become the subject of systematic discrimination and violent policing.

At the same time, the reactions of Tor Sapienza’s residents show the extent to which this emerging topography of political marginalization in Europe’s post-industrial metropoles threads a twin pace with the massive disintegration of the social welfare state and the rise of a precarious underclass that is literally tied to particular places. More than inherent racism, what geographers ought to be looking at, therefore, is the way these hyperghetto’s – the various “casbah’s”, “ghetto’s” and “barbarious outposts” we read about in the media – are the result, rather than the target, of such unfolding urban policies.