What is a border? This question formed the backbone of a talk I was invited to give on ‘Borders & Conflicts in an Age of Globalisation’ – co-organized by CICAM and the Border Research Unit at the University of Nijmegen late 2013. The talk involved references to all kinds of border places, which were, in some ways or another, tangled up in border wars. Using case studies from an edited volume I just published with my colleague Benedikt Korf on the topic, I tried to explain what I mean with that notion – of border conflict – and how one could start distinguishing between different scales of engagement – of state and border, international and local agencies and institutions.

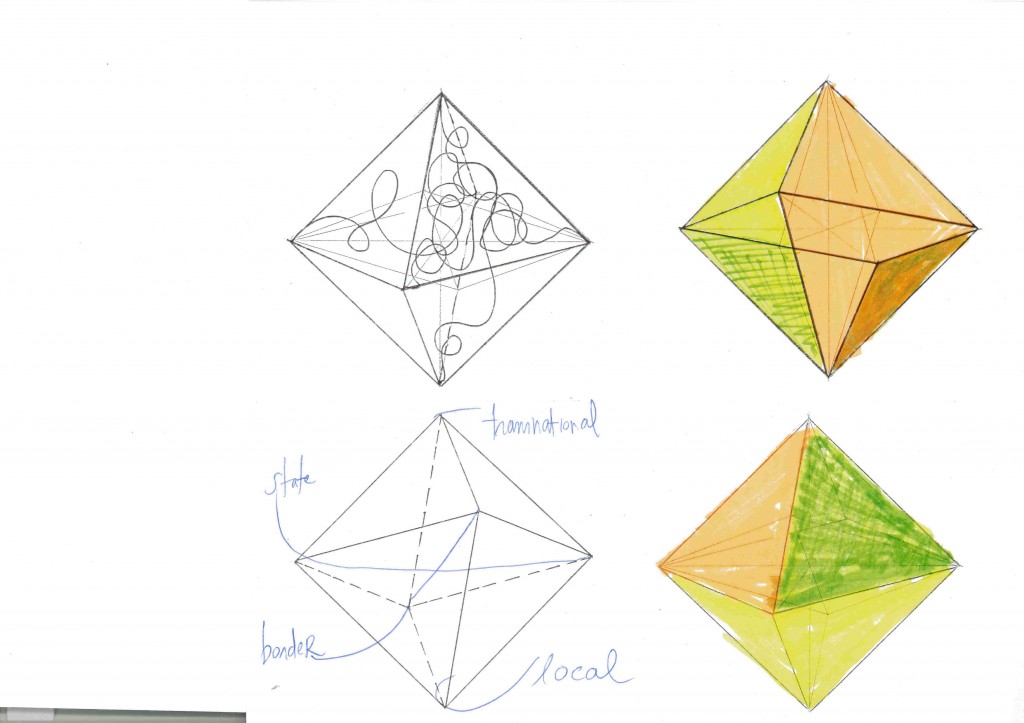

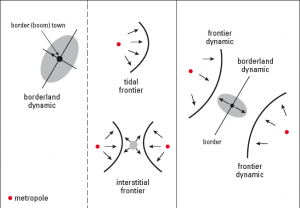

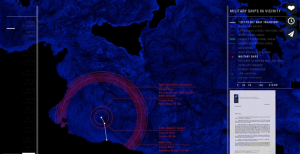

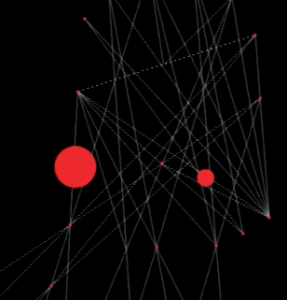

Our main argument at the time was that (1) border polities are political entities that generate their own actions and outcomes – as a result of the (economic, political, socio-cultural) interaction that goes on between different scales, borders may be actually become sites of resistance or accommodation, but which significantly recalibrate power balances between state and border agencies, local and transnational levels of authority; (2) as a result of these tensions, border polities significantly influence political decision-making in the putative ‘centre’. Actually we propose to move away from a state centrist notion of political power that radiates outwards from centre to periphery, towards a more networked understanding of historically produced, relational and dynamic power relations in these border constellations. The graphic summary of this perspective looks more or less like the graphs above.

Topological borders

Since then I came across other contributions that somehow complement this perspective.

I am thinking, for example, of the work of Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson, who, in their recentbook, Border as Method, introduce new ways to discuss what they call the multiplication of labour through border deployment. They analyse, for example, several disciplinary ways of filtering and governing labour mobility, like the “benching” of Indian IT’ers (which involves their temporal insertion and withdrawal in/from the labour market) as well as violent migrant detentions across the EU, Australia, the US and South Asia. Such mechanisms willingly or unwillingly generate a differential inclusion of mobile workers across the globe. They also gradually transform state borders into “decompression chambers”that try to equilibrate, in the most violent of ways, the constitutive tensions that underlie the very existence of labour markets, they write.

The concept of the borderscape, introduced by Suvendrini Perera in the book with the same title, and later taken up by Chiara Brambilla, constitutes another attempt to liberate our (geo)political imagination of border work from its dominant “territorialist imperative”, as Brambilla calls it, and to understand new forms of border deployment that are certainly worth to be investigated.

Artistic Borders

The same kaleidoscopic lens is used in recent artistic explorations, for example during the exhibition at the MAXXI, the National Museum of XXI Century Arts, in Rome from 24-26 October 2014. The focus here is again on the liquidity and elasticity of border regimes and the overlapping jurisdictions underpinning them. Simultaneously these installations open the door towards an emergent migrant subjectivity. One prominent example is the documentary movie Io Sto con la Sposa/On The Bride’s Side co-produced by Antonio Augugliaro, Gabriele Del Grande, and Khaled Soliman Al Nassiry. The journey the Palestinian poet and an Italian journalist undertake across Europe’s borders in the company of their fake wedding crew reveals both the human character of the border – in the form of the bodies, hopes and fears that transgress it. At the same time the wedding journey develops into an interesting masquerade, which both defuses and ridicules the sovereign laws and agencies that actively try to block migrant flows across the continent.

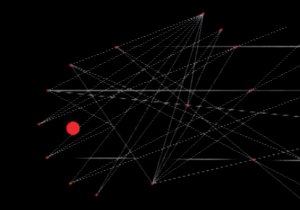

Other prominent artistic explorations include MIG@NET, a European project which – amongst others – developed a video game based on Didier Bigo’s concept of the Banoptikon. The central axis of the game concerns the digitalisation process of migration flows and consequently, the transformations that occur to migrant subjectivity and the urban territories they transgress.

Taken together, the paradigm shift this work proposes is that perhaps, nowadays, it makes more sense to talk about territorial borders in topological rather than topographic terms. Rather than reaching outwards (or extend) from some putative centre, the ability of government to permeate life may be the outcome of a quite intensive mix of distant and proximate actions. Borders are not simple ‘lines in the sand’, says John Williams, but they have become more fluid, more networked, more web-like structures (some prefer to use the Deleuzian notion of agencements).

All of this might just involve a change of epistemology; a change of perspective on what was otherwise, quite erroneously, considered as territorially fixed. Think for example of David Agnew’s observation that with globalization (by which he means both the formation of explicitly global institutions and processes, such as the World Trade Organization, ànd processes oriented towards global agendas and systems but which are still deeply embedded in national power structures, like environmental or fiscal policies), state prerogatives don’t simply dwindle but they are in some way unbundled.

A beautiful case study in this regard is provided by Brenda Chalfin, who talks about new convergence points emerging between the neoliberal restructuring of the Ghanaian state and radical changes in the operation of de facto sovereign authority at the border. Her book also indirectly speaks to my work on Central African traders, in which I try to connect the power of global markets with the reconfiguration of public authority on regional state borders, which both transforms and challenges state power simultaneously at a sub- and a transnational scale.

A beautiful case study in this regard is provided by Brenda Chalfin, who talks about new convergence points emerging between the neoliberal restructuring of the Ghanaian state and radical changes in the operation of de facto sovereign authority at the border. Her book also indirectly speaks to my work on Central African traders, in which I try to connect the power of global markets with the reconfiguration of public authority on regional state borders, which both transforms and challenges state power simultaneously at a sub- and a transnational scale.

Indeed part of the epistemological shift Chalfin is trying to make has to do with integrating the agency of ‘ordinary’ subaltern officials and other public authorities one does not usually associate with such undertakings, but who do significantly rework state authority and institutions from the border inwards, so to say. So rather than stubbornly holding on to border places as either relics of remote backwardness (as state centrists would have it) or sites of outright anti-state resistance (a view James Scott has liked to promote lately), one becomes aware that borders constitute the space of power in numerous ways.

Indeed part of the epistemological shift Chalfin is trying to make has to do with integrating the agency of ‘ordinary’ subaltern officials and other public authorities one does not usually associate with such undertakings, but who do significantly rework state authority and institutions from the border inwards, so to say. So rather than stubbornly holding on to border places as either relics of remote backwardness (as state centrists would have it) or sites of outright anti-state resistance (a view James Scott has liked to promote lately), one becomes aware that borders constitute the space of power in numerous ways.

What all this learns us basically, two things: first, it is not sufficient to simplistically associate territorial state boundaries with fixity – the walls, fortresses and barbed wire we have come to associate with media coverage on migration control and the Israeli-Palestine conflict, for example. Useful as this imagery might be for staging resistance, it does not do justice to the often complex and intricate ways in which sovereign power reaches across multiple scales and spaces.

A second remark that emerges from these studies is that, through technological deployment, borders assume an important temporal dimension as well. By instilling fear and generating precariousness, state borders actively ignite the illegalization of migrant labourers who, as a result, also become “deportable subjects” whose position in both the polity and the labour market is marked by and negotiated through the condition of deportability, even if actual removal is a distant possibility or a threat that has become the background to a whole series of lifetime activities, as Nicholas De Genova and Nathalie Peutz (2010: 146) put it.

A good example of this heterogenization of the border is the ‘archipelago’ of sovereignty Mountz and Loyd talk about with respect to migrant detention facilities in the Mediterranean and in the Pacific. Through this example, they indicate that “[s]tates’ efforts to manage human mobility do not end struggles over territoriality, but rather complicate them [and they] intensify crises of state sovereignty at a range of geographic scales.”

A good example of this heterogenization of the border is the ‘archipelago’ of sovereignty Mountz and Loyd talk about with respect to migrant detention facilities in the Mediterranean and in the Pacific. Through this example, they indicate that “[s]tates’ efforts to manage human mobility do not end struggles over territoriality, but rather complicate them [and they] intensify crises of state sovereignty at a range of geographic scales.”

“Borders, far from serving simply to block or obstruct global flows, have become essential devices for their articulation,” Mezzadra and Neilson write (2014: 3). They’re more accurately described as regulatory devices (Brown 2008: 16-17), or membranes (Petti 2007: 97), which block certain flows of human beings, goods and knowledge, while letting others through. Through such multiple deployments, borders increasingly make their presence feel ‘at a distance’ – as Niklas Rose would say – whether this is through the pixels appearing on the screens of Mediterranean border patrol headquarters, or through the presence of security personal that suddenly pops up to check your identity papers in the park or in a European detention facility in the Libyan desert, or in the form of a US helicopter hovering overhead in the Afghan mountains. I suppose such a vertical and networked understanding about the ways sovereign power continues to make its presence feel ‘at a distance’ promises to enrich the debate about the space of political power in the years to come.